The unreality of promoting the SDGs without a sufficient budget

Grazielle Custódio David

Instituto de Estudos Socioeconômicos – INESC

Brazil made meaningful progress in tackling poverty from 2000 to 2013, largely with the aim of addressing the concentration of wealth and economic power. Most of this progress was a result of public investments in health, education, cash transfer programmes and social protection provision. Not coincidentally, the country’s economy thrived from burgeoning domestic demand. Brazil also set an example in its initial response to the 2008-2009 global economic crisis by increasing social investments,1 which in turn sustained the economy while promoting human rights.

However, these advances are being dismantled due to a series of harmful and severe austerity measures that were put in place by the Government starting in 2015 and were deepened in 2016 and 2017. While aimed at tackling fiscal deficits, these initiatives are increasing socioeconomic inequalities in Brazilian society, with particularly disproportionate impacts on those already disadvantaged. Among the most extreme of these measures, the Constitutional Amendment 95/2016 (CA 95), known as the “Expenditure Rule,” is particularly far-reaching in its harm to human rights and the SDGs.

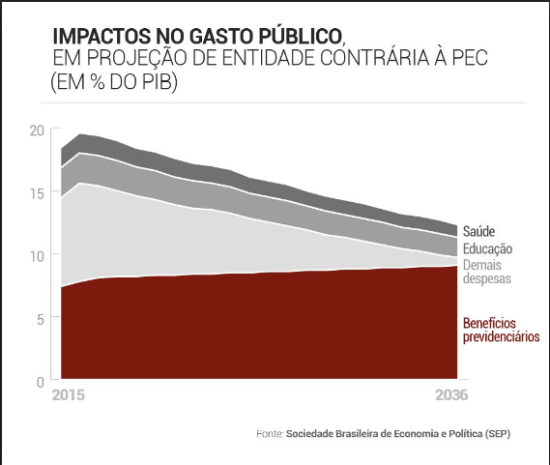

Coming into force in 2017, this Amendment took the unprecedented step of not only freezing real public spending for 20 years but reducing it as a percentage of GDP and per capita. Considering a medium growth rate of GDP of 2.5 percent per year, the federal primary expenditure will go from 20 percent of GDP in 2017 to 16 percent in 2026, and would go as low as 12 percent in 2036 (see Graph 1).

Graph 1: Federal primary expenditure as percentage of GDP and main social policies, 2015- 2036

|

Source: Austeridade e Retrocesso, Sao Paulo, September 20162

Lack of democracy in austere times

By constitutionalizing austerity in this way, any future elected governments, without an absolute majority in Congress, will be prevented from democratically determining not only the priorities of the public budget but also the purpose of the State. That´s one of the most malefic faces of austerity, the narrowing of democratic spaces, with a nation not being able to determine its future and priorities through the electoral process.

Considering not only the future of democracy in Brazil due to the CA 95, it is highly important to analyse the context in which the Amendment was adopted. As Naomi Klein has argued, the relationship between neoliberalism and democracy is a false one, “we have been told a fairy tale on how “this extreme form of capitalism conquered the world. This fanciful version says that it peacefully expanded through democracies that chose neoliberalism freely. However, if we look at the history of the first places where this system was imposed, we’ll see that it was imposed exactly in the opposite way. The crumbling of democracy was necessary for neoliberalism to develop.”3

And that is the context in the case of Brazil. CA 95 only had the chance to be implemented because Brazil experienced a coup. It wouldn´t be possible to democratically introduce that kind of measure in a country with so many people who benefit from redistributive policies that depend on primary expenditure. What was seen during the process that impeached the elected president Dilma Rousseff was shameful, since it was contaminated, legally fragile and permeated by political deals that pollute the three branches of government.4 Two years later, in the run-up to the presidential election, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, from the same party as Rousseff and the top-polling candidate was (and remains) arrested without yet being convicted, in what can be characterized as a political prison.

In a scenario of weak democracy, international agreements are also ignored. With the lack of sufficient budgetary resources to promote the SDGs, Brazil is not respecting what was postulated during the UN Conference “Financing for Development” in 2015, that countries should commit themselves to strength the mobilization and effective use of domestic resources. It is actually taking the opposite course, not considering the revenue side of fiscal policy to improve its fiscal space and not using its domestic resources in a more effective way to accomplish the SDGs.

Brazil is also disrespecting international laws for which states’ margin of discretion in responding to economic crises is not absolute. To be in compliance with human rights standards, fiscal consolidation measures must be temporary, strictly necessary and proportionate; non-discriminatory; must take into account all possible alternatives, including tax measures; protect the minimum core content of human rights [and SDGs]; and be adopted after the most careful consideration with genuine participation of affected groups and individuals in decision-making processes.5 CA 95 implementation doesn´t fulfill any of the standards.

The effects of the “Expenditure Rule” CA 95

With the reluctance of the Executive to determine the necessary resources to fulfill human rights obligations and to implement the SDGs, for example, and considering the reduction of these expenditures as a percentage of GDP it is possible to affirm that Brazil won´t be able to accomplish the 2030 Agenda.6

After one year of the “Constitutional Expenditure Rule”, CA 95 has already begun to disproportionately affect disadvantaged groups. Since its approval, significant resources have been diverted from the most important social programmes towards debt service payments, threatening to exacerbate the already extreme levels of inequality and wealth concentration. These fiscal decisions put at risk the basic social and economic rights of millions of Brazilians, including the rights to food, health and education, the implementation of the SDGs, while also exacerbating gender, racial and economic inequalities.7 After just one year of the new Rule we were able to map relevant budget cuts (see Graphs 2 and 3).

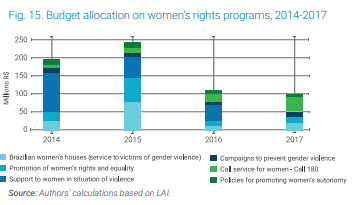

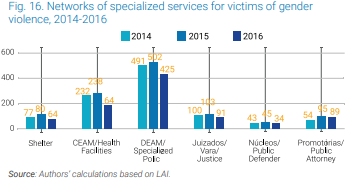

As the budget for policies to prevent violence against women was reduced in 58 percent from 2014 to 2017 (Graph 2), this violence has grown and the specialized services to attend them were reduced (Graph 3), resulting in many women victims of violence receiving no assistance.

Graph 2: Budget allocation on women´s rights programmes, 2014-2017

|

Source: Inesc, CESR, Oxfam Brasil, 2016

Graph 3: Networks of specialized services for victims of gender violence, 2014-2016

|

Source: Inesc, CESR, Oxfam Brasil, 2016

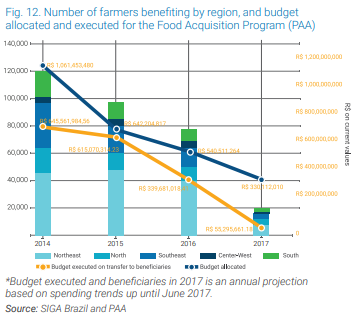

During the same period, a programme to assure food and nutrition security in Brazil, the PAA – Programme of Food Acquisition, had its budget reduced by 75 percent, negatively afffecting small farmers – including indigenous peoples and quilombas, or maroons (see Graph 4).

Graph 4: Number of farmers benefiting by region, budget allocated and executed for Food Acquisition Programme (PAA), 2014-2017

|

Source: Inesc, CESR, Oxfam Brasil, 2016

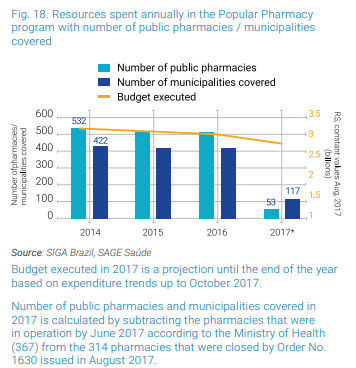

The budget for public pharmacies was also reduced, which resulted in closing down most of them and affecting the most vulnerable municipalities in the North and Northeast regions of Brazil, which relied solely on those pharmacies. Many Brazilians lost their access to medicines in their own cities (see Graph 5).

Graph 5: Resources spent annually in the popular pharmacy programme with number of public pharmacies / municipalities covered

|

Source: Inesc, CESR, Oxfam Brasil, 2016

Further, these fiscal consolidation measures have not benefitted from public participation, as the measures were pushed through in the midst of narrowing opportunities for public scrutiny, accountability, and access to information.

The Executive Rule CA 95 is also anything but temporary, as it will extend far into any future economic recoveries that may occur over the next two decades. These pro-cyclical fiscal measures even run counter to the Government’s own aims of deficit reduction.8

Brazil has also engaged in other actions that characterize almost the totality of measures usually adopted during austerity times: labour reform, proposed pension reform, privatizations, administrative reforms, besides the budget cuts already described. All of these have important impacts on the life and rights of Brazilians.

The alternatives available

Meanwhile, the Brazilian Government has not demonstrated that CA 95 was necessary, proportionate and a last-resort measure, nor that less restrictive alternative measures have been explored and analysed.

In fact, there is solid evidence showing that alternatives—such as more progressive taxation and tackling tax abuses—are readily available.9 A progressive tax reform would be one of the best alternatives to the austerity measures currently in progress. If only one measure was adopted, tax interest and dividends on personal income tax, that could raise the amount of tax collected up to US$ 20 billion yearly.

Other measures such as the prevention of tax evasion could raise collection up to U$ 143 billion yearly; review tax expenditures could raise collection up to US$ 72 billion yearly. Meanwhile the fiscal deficit is around US$ 40 billion, less than what these measures on the revenue side of the fiscal equation could raise.

At the same time, Brazil’s fiscal policy has not been efficient in reducing inequalities in the country. The redistributive capacity of Brazil is too low, when compared with OECD countries and some Latin American countries.10 An important explanation for this remains the problems with the tax system, since it is highly regressive, with more than 55 percent of tax revenue coming from consumption, instead of direct taxes, such as on income or property. The result of that the tax burden is proportionately higher on the poorest. That is one extra reason to do a progressive tax reform.

Also, as the International Monetary Fund (IMF) states in its 2018 Fiscal Monitor, countries are urged to avoid pro-cyclical policies during fiscal crises.11 Therefore, counter cyclical policies could produce better results, by investing in social and infra structural areas. That would be financed by progressive taxation and by the results of the growth raised by the investments made.

Without adopting these alternatives measures, and yet maintaining the policy of austerity, it is hard for any government to implement the SDGs and international agreements such as the ones on Climate Change, among others. That makes Brazil go on the opposite way of history, human rights, international law and other international covenants.

Notes:

SEP, Fórum 21, FES, Plataforma Política Social, 2016. Austeridade e Retrocesso: Finanças públicas e política fiscal no Brasil. Available at: http://brasildebate.com.br/wp-content/uploads/Austeridade-e-Retrocesso.pdf

2 Friedrich Ebert Stiftung, Forum 21, Plataforma Politica Social, Brazilian Society of Political Economy, Sao Paulo, available at: http://library.fes.de/pdf-files/bueros/brasilien/12834.pdf

3 Naomi Klein, 2016. Interview on The Dawn with Rafael Tatemoto of Brasil de Fato: ‘Brazil´s democracy is under attack’. Available at: http://www.thedawn-news.org/2016/06/03/brazils-democracy-is-under-attack-says-naomi-klein/

4 Inesc, “Nota pública: Golpe parlamentar no Brasil – página infeliz da nossa história.” Available at: http://www.inesc.org.br/noticias/noticias-do-inesc/2016/agosto/pagina-infeliz-da-nossa-historia

5 Committee on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (CESCR), “Public debt, austerity measures and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights 2016” (UN Doc. E/C.12/2016/1).

6 A. Cardoso, G. C. David, and I. Pietricovsky, "Utopia or Dystopia? The sustainable development goals in Brazil and in the world,” Social Watch Report, 2016. Available at: http://www.socialwatch.org/node/17748

7 Inesc, CESR, Oxfam Brasil, “Human rights in times of austerity,” 2016. Available at: http://www.inesc.org.br/headlines/biblioteca/publicacoes/outras-publicacoes/publicacoes-em-ingles/human-rights-in-times-of-austerity/view

8 A. Albano, “Uma crítica heterodoxa a proposta do novo regime fiscal,” 2017 (PEC No. 55 de 2016). Available at: https://revistas.fee.tche.br/index.php/indicadores/article/view/3883/3840

9 Inesc, CESR, Oxfam Brasil, “Human rights in times of austerity,” 2016.

10 IMF, Fiscal Monitor 2017: “Tackling inequality”; available at: http://www.imf.org/en/publications/fm/issues/2017/10/05/fiscal-monitor-october-2017

11 IMF, Fiscal Monitor 2018: “Capitalizing on good times”; available at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/FM/Issues/2018/04/06/fiscal-monitor-april-2018