COVID-19: The great revealer

Katherine Scott1

Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives (CCPA)

COVID-19 ground the world’s economy to a halt as countries locked down to prevent the pandemic’s spread. Myriad airplanes no longer fly overhead. Global supply chains have stalled. Lives have been disrupted; lives have been lost. Canada is still reeling from this global pandemic, which has exacerbated long-existing inequities.

Of course, a pandemic of this scale was never a question of ‘if’ but a question of ‘when’. Lessons from SARS in the early-2000s taught us that we should prepare. Public health officials warned, year in and year out, that we should prepare. But government austerity agendas—fuelled by neoliberal ideology that privileged the “free market” over public health and community wellbeing—left us wholly unprepared. Those groups and communities least able to shoulder the social and economic fallout of COVID-19 are now struggling under its weight.

The COVID-19 pandemic is putting Canada’s commitment to the United Nations Social Development Goals (SDGs) to the test. This pandemic is forcing us into a new chapter of history. We will be judged by what we do next. And we will be judged by what we fail to do.

Entering the pandemic without a safety net

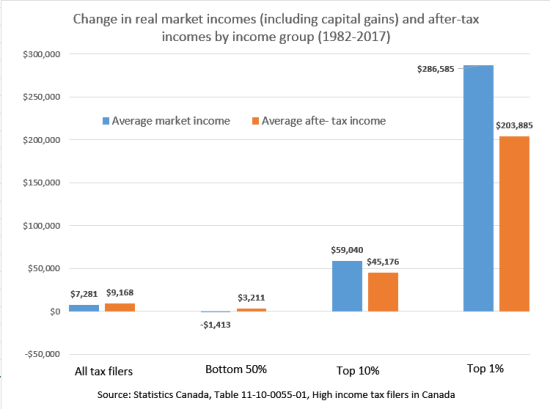

Canada’s economy reflects the global trend towards growing concentration of wealth and income among those at the top of the income ladder and the stagnation of incomes for everyone else.

Inequality in Canada may be less extreme than in the U.S., but it grew at a faster rate here between 1997 and the onset of the 2008-09 recession, during a time of robust economic growth and job creation.2 Since 2009, the market income share of Canada’s top 1% has declined slightly (from 15.3% in 2007 to 13.2% in 2017),3 as has their share of wealth.4 However, the richest 1% of families still hold 17% of the country’s net wealth 5 and the market incomes of top earners continue to outpace other income groups.6 The pandemic has only deepened these graphic disparities.7

By contrast, the bottom half of Canada’s earners actually saw their market incomes shrink by 14% between 1982 and 2017, when adjusted for inflation—a reflection of both an increasingly polarized labour market and rising wage inequality. The real market incomes of all tax filers grew by 20% over this period, while the market incomes of the top 1% almost doubled (97%).

|

Only government transfers—in the form of seniors’ benefits, employment insurance, child benefits and the like—saved the bottom half of Canadians from being materially worse off today than a generation ago. But those transfers are not as effective in offsetting income disparities as they were in the 1980s and early-1990s.8

“The combination of greatly increased concentration of income at the top and reduced chances of getting there for the rest signals a society that is substantially less equitable, inclusive and fair than it was three decades ago.”9

We all live with the damaging consequences of persistent inequality in the form of poorer health, lost potential, higher social costs, and weaker community ties. The costs are most acute, however, for Indigenous peoples, racialized communities, people with disabilities, and other marginalized communities that consistently report lower levels of income, employment, and access to the factors that promote good health and well-being.

Racialized Canadians, for instance, experience higher unemployment rates, lower earnings and employment segregation in the labour market and, in turn, have higher levels of poverty than those who are non-racialized (20.8% compared to 12.2% in 2015).10 Large numbers of Canadians with disabilities are forced to rely on the meagre incomes offered through provincial social assistance because of huge barriers in the labour market and lack of accommodations.11 Levels of poverty among Canadians with disabilities are one-and-a-half times higher than among those without disabilities.12

COVID-19: The great revealer

The inequities that were baked into Canada’s system have been graphically exposed and exacerbated by the COVID-19 pandemic. Canada was initially slow to take action, waiting until mid-March to close the borders to foreign nationals and restrict non-essential travel. “Beginning with Quebec on March 14th, provinces and territories began to issue public health emergencies, closing schools, limiting the size of public gatherings to smaller numbers, and eventually shutting down all but essential services.”13 Governments began the scramble to secure needed supplies, medication, and personal protective equipment, as stockpiles were low— the result of years of neglect— and precarious supply chains.

Confirmed cases of the virus started to rise in early April and began to level off in June, not before more than 8,000 people had died, the vast majority of whom were in long-term care homes.14 While hospitals took quick action to prepare for an expected surge in the number of patients, the tragedy unfolded in nursing homes, mostly in Quebec and Ontario, which were sidelined in the country’s planning and left wholly unable to deal with the COVID-19. According to the Canadian Institute for Health Information, long-term care residents accounted for 81% of all reported COVID-19 deaths in Canada as of May 25th, far outpacing the average of 16 other OECD countries (at 42%).15

Canada’s long-term care system was already struggling before the arrival of COVID-19, drained and strained by austerity measures over the past two decades.16 The virus moved through facilities, preying on well-documented vulnerabilities: a growing reliance on a sub-contracted labour force whose members work multiple jobs to make ends meet as well as precarious employment conditions such as fewer workers, more part-time hours, high turnover, heavy workloads, thin protections, poor wages, and benefits, which work against quality care and recruitment.17 Canada’s failure to introduce specific prevention measures for the long-term care sector when the pandemic hit—and deep-seated challenges related to funding and jurisdiction in Canada’s highly decentralized political system—resulted in Canada’s shamefully high fatality rate among vulnerable seniors.

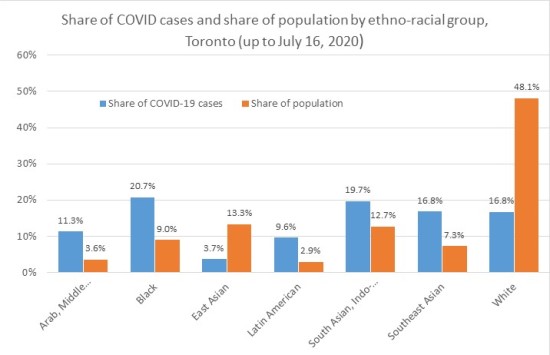

Canada has had a measure of success flattening the curve through the spring and early summer. As of late July, approximately 115,000 cases of COVID-19 had been reported, with almost 9,000 dead and at least 6,000 cases were still active.18 But, as elsewhere, the burden of the illness is weighing most heavily on vulnerable communities. New research from Toronto echoes findings from Montreal19, revealing that racialized people are overrepresented both among reported cases of COVID-19 and those who have been hospitalized. And 51% of reported cases were among people living in low-income households, compared to 30% of the city’s general population.20

|

Source: City of Toronto, COVID-19 infection in Toronto: Ethno-racial identity and income. Includes only cases with valid data.

Like the fate of long-term care residents, stark disparities in the rate of infection evident in Toronto’s public health data were not unexpected either—the result of long-established disparities across a range of social and economic indicators. The communities that were hardest hit were also the communities with high concentrations of racialized people, newcomers to Canada, the unemployed, and people living in cramped, unsuitable housing with limited access to health and social services.21 These communities were home to many essential workers who were working as nurse aides and orderlies, as cashiers and shelf stockers, as truck drivers and workers in food processing plants.22 For these workers and their families, the lockdown made little or no difference. While community transmission in high-income neighbourhoods started to drop almost immediately in late March, reported infections in the poorest and most racialized neighbourhoods didn’t begin to trend down for two months.23

Inequality threatens to worsen as an outcome of COVID-19

The public health crisis continues as researchers around the world search for an effective vaccine and approach to treatment. In Canada, the pandemic necessitated massive federal government spending to protect people and communities. This will result in a deficit of over $340 billion this year24—the deepest deficit in Canada’s history. It’s due to necessarily higher spending on emergency support programs such as the Canada Emergency Response Benefit, the Canada Emergency Wage Subsidy for employers, and investments to help provinces, territories, and Indigenous communities limit the spread of COVID-19 and respond to the health needs of Canadians. These programs have played an essential role in sustaining households—and the broader economy—in the face of mass unemployment precipitated by shutdown and the sizable pre-existing gaps in Canada’s social safety net.

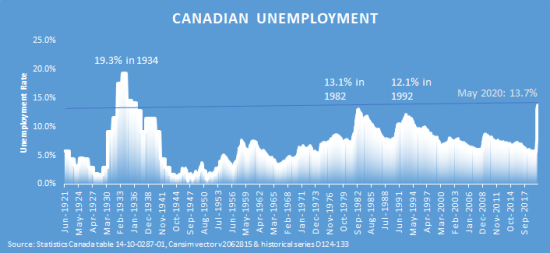

|

Three million Canadians lost their jobs and another 2.5 million lost between 50% and 100% of their working hours between February and April—three out of 10 Canadian workers.25 These shocking Depression-level job impacts were required to flatten the curve of COVID-19’s spread, but the economic burden has not been equally shared. Employment losses have been higher amongthose employed in precarious jobs and those in the lowest hourly wage bracket. In the first two months, 30.2% of temporary workers lost their jobs, almost double the average loss of 15.7%. Four out of 10 employees earning less than two-thirds of the 2019 median hourly wage (38.1%) lost work, as did one in four of those paid by the hour (25.1%).26

In Canada, the lowest earning group is overwhelmingly female and highly racialized. Fully half (52%) of all low-wage workers earning less than $14 an hour or less were laid off or lost the majority of their hours between February and April. This includes 58% of low-wage women and 45% of men in the same earnings bracket. For those in the top earnings group, with wages of more than $48 an hour, only 1% lost employment or a majority of hours. Among the top 10% of earners, 7% of women lost employment and while employment for men in this top income group actually increased by 2%.27

Employment losses were particularly high among newcomers to Canada (those who have immigrated to Canada within the last 10 years), a large majority of whom are racialized28 and working in precarious jobs that carry a high risk of exposure to COVID-19 in sectors such as retail, food, and accommodation—all hard hit in the downturn.29 Over one-third of recent immigrants (-37.7%) who were employed in February 2020 had lost their job or the majority of their working hours by the end of April—eight percentage points above the losses posted by Canadian-born workers (-29.1%).30

With the reopening of the economy this spring, more people are back at work and others are picking up hours. But, like the downturn, the recovery is proving to be uneven, demonstrating “the brutally unfair concentration of this recession on the backs of those who can least afford it.”31 This situation creates numerous challenges for Canada moving into what will probably be a slow and sporadic recovery.

The July jobs report from Statistics Canada shows that since April, the labour market has now recovered about 55% of the three million jobs lost to the pandemic, bringing employment to within 1.3 million

(-7.0%) of its pre-COVID February level. While these gains are important and provide hope for long-term recovery, the number of the unemployed and underemployed in Canada remains at historic levels. In July, 2.2 million Canadians were out of work—1.05 million above the levels posted in February—and 972,000 Canadians were working less than half of their regular hours.32 Women represent just over half of this number (52.7%).

Most of July’s employment growth was in part-time work, as it has been since May. Part-time work is now closer to its pre-COVID level (-5.0%) than full-time employment (-7.5%), but many more Canadians are involuntarily working part-time.33 The summer boost in part-time work in hard-hit industries, such as retail and food services, has spurred the rise of employment among low-wage workers, but the rate of recovery continues to lag behind higher-paid employees by 12 percentage points (85.4% vs. 97.4%).34

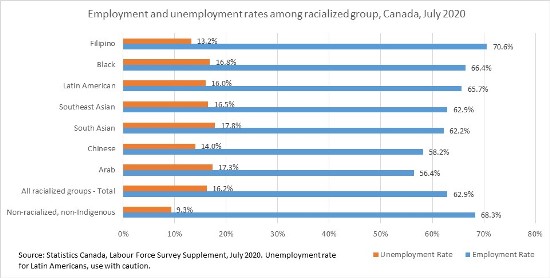

The recovery is also unfolding at a different pace for racialized people. South Asian (17.8%), Arab (17.3%), and Black (16.8%) Canadians all reported higher rates of unemployment in July than non-racialized Canadians (9.3%), which suggests that pre-existing disparities are in the process of becoming further entrenched. Just as troubling, the employment gap between racialized and non-racialized groups, effectively non-existent pre-COVID, has grown considerably and stood at 92.1% in July.35

|

Women risk losing ground due to COVID-19

The impact of COVID-19 on women’s work has been so immense, there is a threat to equality gains secured decades ago. Between February and May, the gender employment gap fell sharply, to 84.7%, due to the massive loss of women’s employment in the first two months of the pandemic and the quick rebound in male jobs in sectors such as construction. Women’s employment has since improved, notably in part-time work, but women have only recouped roughly half of February-April employment losses (53.7%) and less than one-third of full-time employment losses (31.0%).36

As of July, men in the core-age group of 25 to 54, who were least affected by the shutdown, had recouped 63.5% of early employment losses while women in this age group had recouped 56.8% of their losses. Young women (aged 15 to 24) were the furthest from their February employment level (82.1%), followed by young men (83.1%) in the same age group.37

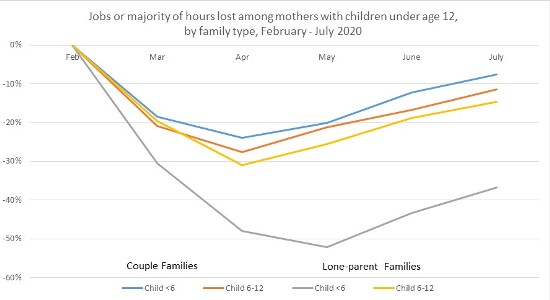

Mothers have an equally long road ahead. From February to April, 620,000 mothers with children under age 12 were affected by the COVID-19 economic shutdown. This included a drop in employment of 235,000 and a COVID-related increase in absences from work of 385,000.38 By mid July, the total number of affected workers stood at 285,000, or 12.6% of all mothers with young children who were working in February.

Lone-parent mothers with children (0-12 years) have experienced the greatest challenges compared to other parents, posting the largest job losses and the slowest recovery. By mid-July, they had recouped only 29.6% – or less than one-third – of their February-April employment losses. The situation among lone-parents with children under six was especially dire, having recouped only 8.6% of employment losses.

Rates of employment among mothers with children (aged 0-12) living in couple families are also still much lower than in February, especially among those with school-aged kids (6-12 years). This coincides with an increase in the number of mothers (both lone-parents and mothers in couple families) who are employed but absent from work on leave. This number more than doubled between February and April and as of July was still twice as high as in February.

Employment loss is only part of the picture. When the pandemic hit, there was also a significant rise in the number of mothers with children under 12 working less than half of their usual hours, more than doubling between February and April. The share of mothers working reduced hours has fallen slowly through the spring, but still exceeds February levels by 50%, effecting one in ten working mothers as of July.

|

Source: Feb - July 2020 Labour Force Survey PUMF, calculations by D. Macdonald. Excludes self employed.

These are stark figures. Yet they do not capture women who have left the labour market altogether and are now at home caring for children or others who are ill with no prospect of immediate return to paid work. Among core-aged women (aged 25-54 years), the number of women outside of the labour market increased by 425,000 (or 34.1%) between February and April. By July, the size of this group was smaller, but still in excess of 110,000 workers—roughly three-quarters (74.0%) of the way back to February levels. Not everyone is finding their way back in the labour market.39

The lack of coherent or safe plans to reopen child care centres and schools in Canada has created significant barriers for mothers wanting to re-enter the workforce. Social norms and the traditional caregiving roles of women, which have contributed to gender gaps in pay, are now pushing mothers, rather than fathers, out of the labour market and into full-time caregiving and home schooling.

The economic security of many is hanging by a thread. In past recessions, women flooded service sector jobs to stabilize family incomes devastated by losses in typically male-dominated, goods-producing industries. With the shutdown of broad swaths of the service sector, this strategy isn’t an option. Without accessible and affordable child care on offer, as well as other health and housing supports, many women simply won’t have the choice.

The widening employment gap between women and men further represents a huge threat to women’s economic security and that of their families. Prior to the pandemic, women earned 42% of household income and were, on average, responsible for almost half of household spending.40 The precipitous collapse in employment will inevitably lead to greater financial hardship, not just in the coming months, but, for years to come.

The speedy implementation of the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit, a flat benefit of $500 a week, stabilized the household incomes of millions. But this program is slated to end in October, leaving an estimated 4.7 million people— the majority of whom are women—up in the air. That’s 10 times the number of unemployed in February.41 In late August, the federal government announced one-time changes to the Employment Insurance system, which will temporarily ease eligibility requirements and provide a higher benefit floor of $400 per week. The government estimates that these measures will facilitate the transition of approximately three million workers from the Canada Emergency Response Benefit to Employment Insurance, boosting coverage the 40% of unemployed workers who are eligible. Three new emergency benefits have also been proposed to support the self-employed and gig workers who fall outside of Employment Insurance and the mostly women caregivers who must leave employment to provide care.42

RBC Financial estimates that, absent a second wave of the virus (a big if), employment will recover to within 2.5 percentage points of pre-COVID-19 levels by the fourth quarter of 2020. But the extent of the recovery will vary hugely from industry to industry. Employment in accommodation and food services, where women dominate, may take years to recover—an example of a devastating “L” shaped recovery. In contrast, male-dominated manufacturing, construction, and natural resources jobs are already springing back, following the much more desirable “V” shaped path.43

Without focusing recovery efforts on the needs of Canadians who are experiencing the greatest barriers, progress towards greater equality will be rolled back decades and the recovery itself will be prolonged, with hugely damaging consequences for the whole society.

A progressive, just recovery

COVID-19 exposed the impossibility of a healthy economy without a healthy society. The status quo is no longer an option. This is our chance to bend the curve of public policy toward justice, wellbeing, solidarity, equity, resilience, and sustainability. This is our chance to advance the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. These are not just words; these are the conditions upon which we rebuild.

Canada’s federal government has acknowledged that Social Development Goals (SDGs) are of “heightened importance” in the context of the pandemic. Canada looks to ways “to protect against the long-term shocks that have impacted our economy, society, and environment and collectively turn our attention to rebuilding a more inclusive, resilient and sustainable Canada.”44 It remains to be seen whether Canada’s recovery plan will achieve these goals.

The pandemic represents a golden opportunity to chart a course toward equity and the creation of a caring economy that includes updated public services for the 21st century, a modern income security system tailored to today’s social, economic and environmental risks, a meaningful and sustained program of action towards a zero-carbon future, and the realization of Indigenous rights and self-determination.

Creating a vibrant caring economy:

COVID-19, which required the imposition of emergency pandemic control measures, has demonstrated how economically and socially precarious many Canadians—and the services they depend on—are after 30 years of austerity and privatization. The pandemic has also exposed the systematic undervaluing of paid and unpaid care work. Pandemic emergency measures prioritized collective public good. Recovery planning can continue to do so by removing gender and racial bias from economic and social policy and by centring the experiences of diverse and marginalized communities of women in recovery planning.

Now is the moment to revitalize social and physical infrastructure, to create a system of comprehensive, high quality, publicly managed caring services that reach all Canadians across the country. Investing in social infrastructure has the added benefit of paying for itself over time,45 through increased employment and earnings, reduced income security benefits and emergency services, and healthier communities. Child care, long-term care, and services for victims fleeing violence are just three of the sectors that demand transformative change.

Early learning and child care: Building an affordable and accessible public early learning and child care plan is an immediate priority. It has taken a public health crisis for the essential role of early learning and child care to be widely recognized, and for the fragility of Canada’s existing provisions to be laid bare. Seven out of 10 Canadian licensed child care centres laid off all or part of their workforce during the emergency response phase of the pandemic, and more than one-third of the centres are now uncertain the ability to re-open. Federal leadership, including bold, accelerated federal spending, is needed to expedite Canada’s move from the market-based provision of early learning and care to a publicly managed and fully publicly funded system.

Long-term care: Health-care workers paint a picture of a system that was already struggling before the coronavirus hit,drained and strained by austerity measures over the past two decades. Allowing long-term care and home care support to be structured as low-paid, precarious work provided by women who can’t afford to stay home when they’re ill has proven a disastrous choice.46 The expansion of large private chains that generate sizable profits through short staffing, lower wages, few (if any) benefits, and no pensions has exponentially compounded the risk to vulnerable residents and workers.47 Canada urgently needs to make new investments tied that are to national standards of care and employment as well as reliable access to training, personal protective equipment, and related supports.

Violence against women/gender-based violence services: The COVID-19 pandemic and the emergency responses that it has necessitated have shone a much-needed spotlight on violence against women and gender-based violence, while placing additional strain on already taxed anti-violence services.48 Government-mandated stay-at-home measures both heightened risk for women and children in abusive homes and reduced their ability to leave for the safety of a women’s shelter. The closure of physical spaces and the shift to remote services have also created unique access barriers to sexual assault centres49 and other services that support victims experiencing violence. The recovery response must be sufficient to not only sustainably fund the sector and its continuing growth, but to also foster violence prevention and the expansion of transitional housing to induce the long-awaited reduction in rates of violence. This is the moment to bring in two long-promised national action plans to prevent and combat all forms of violence against 1) First Nations, Inuit, and Métis women, girls, and Two-Spirit Peoples (to be led by Indigenous women’s organizations), and 2) all women and girls.

Investments in Canada’s care economy should be tied to an explicit strategy of ending the privatization of care and expanding the capacity of public, non-profit care services and facilities to meet community need. This should include access to non-profit sector stabilization funds to support direct operational and service adaptation costs. Raising federal, provincial, and territorial employment standards is also essential to ensuring access to living wages, paid sick days, stable employment, and the right to refuse unsafe work—for all workers.

Building a modern income security system:

The federal government took several important steps in the first years of its mandate to tackle poverty. It reformed and enhanced Canada’s child benefit system, boosted benefit levels for poor single seniors, and introduced a new Canada Workers Benefit. These measures lifted almost half a million people out of poverty.50 In 2018, the government released its poverty reduction plan which, for the first time, set targets for reducing poverty, defined an official poverty line, and established a framework and a process for reporting publicly on progress.51

Yet when the pandemic hit, the glaring holes in Canada’s social safety net were evident for all to see. Canada’s unemployment insurance system could not reach enough people. It could not pay them enough nor get money out quickly enough. Large groups of workers did not have access to paid sickness leave. There were no job retention programs in place to help offset the cost of wages for employees who working reduced hours on a temporary basis. There were no supports in place to help families with caregiving as child cares, schools, and community-based programming shut down and revenues dried up. Nor were the resources available to meet the needs of marginalized communities facing a public health emergency of this magnitude.

The federal government responded quickly with an emergency benefit, the Canadian Emergency Response Benefit, which delivered a flat taxable benefit of $500 per week to workers who were suddenly without work, on reduced schedules, sick, or caring for family. This program extended support to the self-employed and precarious workers who were most impacted by the economic crisis but ineligible for Employment Insurance under its stringent qualifying rules. Other one-time payments were made to boost the incomes of low-income households, families with children, seniors, and people with disabilities. The Canada Emergency Student Benefit provided support to students and new graduates who were not eligible for the Canada Emergency Response Benefit or Employment Insurance.52,53

The roll-out of these emergency measures offer important lessons for strengthening Canada’s income security system to better enhance and protect the economic security of Canadian households and tackle the income inequality gap.54 This includes taking action to:

- Reform the Employment Insurance program by bringing in lower and uniform eligibility standards to ensure that precarious workers are not left behind, making permanent a new higher income floor,55 and creating a more agile delivery mechanism. In combination with enhanced supports for re-training, upgrading, and literacy, the Employment Insurance system will function more effectively as the automatic economic stabilizer that it is supposed to be.

- Raise the incomes of those living in deepest poverty by uploading social assistance to the federal level and establishing a minimum income guarantee to apply to all federal income security programs to ensure adequate levels of income support, taking into account the needs of the most vulnerable and caregiving obligations. This includes related reforms for existing programs targeting seniors, people with disabilities, low-income workers, post-secondary support for students, and other marginalized Canadians.

- Amend the federal poverty reduction strategy to alleviate disproportionate levels of poverty in racialized and Indigenous communities, which are likely to increase because of the economic downturn from COVID-19.

- Improve the earnings and working conditions of those in the low-wage workforce by setting a federal minimum wage of $15 per hour for workers under federal jurisdiction, granting full labour rights and protections to migrant workers, and bringing in robust pay equity and employment equity provisions to tackle longstanding segregation and disparities in the labour market.

Taking action towards a zero-carbon future:

Governments at all levels have taken unprecedented action to respond to COVID-19 and that same level of ambition and speed must also be applied to the zero-carbon transition. We cannot afford to scale back investment or redirect political will from the vital project of phasing out fossil fuels and building inclusive, green communities. Canada needs a national decarbonization strategy that charts a course to a net zero-carbon economy, including a clear timeline for the regulatory phase-out of oil and gas production for fuel by 2040, and provides a framework for critical public investments to reach this goal.

Significant investment is needed to spur the creation of value-added jobs across the economy, including in female-dominant care sectors, to rebuild manufacturing capacity, and to support the transition to a zero-carbon economy. This should be grounded in the principles of decent work and environmental sustainability, providing support to workers and communities that are negatively affected by the move to a zero-carbon economy.

This will involve support for high-impact green infrastructure projects in the communities where they are needed most, supporting the shift to renewable energy and increased energy efficiency through electrification projects, energy-efficient construction and retrofits, public transportation and the like. Such investments should also provide the opportunity to promote local and social procurement, including through Community Benefit Agreements that address racial, gender, and other inequalities in the labour market.

Additional funds are also needed to support nature-based climate solutions, including habitat restoration, the development of natural infrastructure, and the creation of terrestrial and marine-protected areas, including Indigenous protected areas and the Indigenous Guardians Program.

Upholding Indigenous rights and self-determination:

Canada has been called out repeatedly by the UN Human Rights Council56 and other agencies for its failure to address the glaring gap in living conditions and quality of life between Indigenous peoples and the non-Indigenous population.

Indigenous peoples are three times more likely to live in housing that is in need of major repairs (a problem that is particularly acute for the Inuit population in the far north of Canada)57 and more than 50 First Nations communities live without safe drinking water.58 Indigenous peoples experience higher than average rates of incarceration59 as well as significantly higher rates of violent victimization.60 The National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls—established in response to repeated calls from Indigenous families, communities, and organizations—concluded that the Canada’s federal, provincial, and municipal laws, policies, and practices had created an infrastructure of violence that has led to thousands of Indigenous women and girls murders and disappearances, as well as grave human rights violations.61

Redressing past wrongs and establishing an equitable and just relationship with First Nations, Métis, and Inuit people is fundamental to meaningful reconciliation set out in the 2015 Truth and Reconciliation Commission.62 Federal investments in Indigenous programs over the past five years have begun to chip away at the issues but a holistic and thorough response is still required to facilitate the fulsome participation of Indigenous peoples in the COVID-19 recovery.

Funding for health and social services, education and employment, physical infrastructure, and support for core governance capacity is critical to addressing the deep roots of persistent poverty and marginalization. Immediate action is also needed to launch a comprehensive, appropriately resourced National Action Plan to prevent and combat all forms of violence against First Nations, Inuit, and Métis women, girls, and Two-Spirit Peoples to be led and developed by Indigenous women’s organizations.

Towards a progressive fiscal recovery:

To meet the urgent demands of people, businesses, and the health care sector during the emergency response phase of COVID-19, the federal government took immediate leadership and implemented programs and income supports that saved lives. The inevitable result is that the federal deficit is estimated to be $343 billion this year.63

Compared to the size of the Canadian economy, even factoring in a hit to GDP this year due to the pandemic, Canada is still in better shape than it was for much of the 1990s. Heading into the pandemic, federal program spending in 2018-19 was 14.6% of GDP—an increase of 1.8 percent points from 2014-15, but still considerably shy of post-war levels. On the other side of the ledger, federal revenues are also near all-time lows relative to GDP. Revenues as a share of GDP, at 15.0%, were a percentage point higher than in 2014-15 but still below the 17% they averaged from 1966-2006. 64 This 2% difference represents lost revenue of $50 billion in 2019 alone.65

We must emphasize what this federal debt has made possible: unlike previous financial crises, Canada has avoided mass bankruptcies for families and businesses, at least for the time being. Most of this year’s federal deficit was incurred to pay for various income supports that allowed families to continue to meet their bare minimum needs, including housing and debt payments, during the shutdown. Without that help, the economic shock on households and businesses would have been devastating. Historically low interest rates have also strengthened the government’s hand.66

That said, decades of tax cuts have left the government with fewer revenue tools at its disposal. There’s a lot of scope to increase revenues and reduce inequalities across the board by making the tax system more progressive and by increasing revenues to support expanded public services.

Closing expensive tax loopholes that benefit mainly Canada’s wealthiest income earners, including the stock option deduction and preferential taxation of capital gains, would generate substantial revenues. Likewise, an inheritance tax similar to the one in the U.S. and many other OECD countries could generate billions a year, depending on the design.67 An excess profits tax, such as the one that Canada had during the world wars, would be wholly appropriate for the large corporations making massive profits as a result of the pandemic.

The introduction of a digital services tax on large multinational e-commerce firms is particularly pressing. It would level the digital playing field and ensure that these unscrupulous tax dodgers pay their fair share.68 Greater regulation of tax avoidance is also key to Canada’s recovery. Canada currently loses an estimated $15 billion in tax avoidance each year. Over $300 billion dollars are parked in international tax havens. Imposing a 1% withholding tax on corporate assets held in known tax havens or putting a cap on interest payments to offshore subsidiaries would help to recoup these revenue losses.

Canada’s price on carbon is an important, albeit modest, means for meeting Canada’s medium-term greenhouse gas emission reduction targets and international obligations under the Paris Agreement. But a higher carbon price floor is needed in order to reach our 2030 greenhouse gas emission target. Revenues generated through this charge—and the cancellation of fossil fuel industry subsidies—could be used to offset the impact of the higher tax on lower-income households and to support critical investments in renewable energy, energy efficiency, public transit, and transition measures for the most affected workers and their communities.

Conclusion

Canadian governments—and the people who nudge them forward—are literally writing history right now. The choices we make will define generations to come, just as similar turning points in history created new moments of solidarity, social justice, greater equality, and community wellbeing.

The world wars, the Great Depression, and the growth of the labour movement forced Canadian governments to re-imagine the social contract. Canada reduced income inequality and grew a middle class out of that contract. But many of those gains have been unravelled over the past generation and there was so much unfinished work to be done before the great unravelling began.

A global pandemic is a sobering reminder that public priorities matter; that governments have an active role to play in ensuring the public’s health and safety; that we need to act in social solidarity to invest in lasting changes that will make Canada more resilient, improve community well-being, ensure that inequality is reduced, support the most marginalized and disadvantaged, and improve the quality of life of all Canadians.

Now is the moment to address issues that have been neglected for more than a generation: poverty; declining infrastructure; the lack of potable water, decent housing and other infrastructure in Indigenous communities; and the immediate and urgent need to address the climate emergency. With a stronger, more equitable fiscal foundation, Canada will be in much better position to weather the fallout of the pandemic the coming years and the economic, social and environmental challenges that will follow. Transformational investments in Canadian public services and infrastructure will lay the foundation for shared prosperity for generations to come.

Notes:

2 The richest one percent of earners in Canada accounted for 32% of all income gains between 1997 and 2007. CCPA (2016), “Poverty and Income Inequality,” Time to Move On: Alternative Federal Budget 2016. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives, p. 98.

3 Income is pre-tax from all sources including capital gains. Statistics Canada, Table 11-10-0055-01, High income tax filers in Canada.

4 Statistics Canada, Table 36-10-0585-01, Distributions of household economic accounts, wealth, by characteristic, Canada, annual.

5 Carlotta Balestra and Richard Tonkin (2018), “Inequalities in household wealth across OECD countries: Evidence from the OECD Wealth Distribution Database,” Working Paper 88, Statistics and Data Directorate, OECD. For a discussion of wealth concentration in Canada, see: David Macdonald (2018), Born to win: Wealth concentration in Canada since 1999. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

6 Statistics Canada, Table 11-10-0055-01, High income tax filers in Canada. Among the top one percent, earnings (including capital gains) has effectively doubled since 1982, reaching $581,700 in 2017.

7 The $2 per hour boost in pay for “essential workers” – already cancelled – pales in comparison to the bonuses paid out to grocery store executives. Darren Major (2020), “MPs grill grocery store execs over pandemic pay cancellations,” CBC News.

8 John Myles and Keith Banting (2013), “Inequality and the fading of redistributive politics,” in Inequality and the Fading of Redistributive Politics, Vancouver: UPC Press, 2013.

9 David Green, Craig Riddell and France St-Hilaire (2017), “Income inequality in Canada: Driving forces, outcomes and policy,” Income Inequality: The Canadian Story, Green, Riddell and St-Hilaire (eds.), Institute for Research on Public Policy, p. 25.

10 Sheila Block, Grace-Edward Galabuzi, Ricardo Tranjan (2019), Colour coded income inequality, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives. Poverty rates calculated using the Low Income Measure – After Tax.

11 John Stapleton (2013), The “welfarization” of disability incomes in Ontario. Metcalf Foundation.

12 Statistics Canada, Canadian Survey on Disability, 2017. Low income measure used: Market Basket Measure.

13 Sean Clarke, Carter McCormack and Wisha Asghar (2020), Recent Developments in the Canadian Economy, 2020: COVID-19, third edition, Statistics Canada, Catalogue no. 11-626-X - 2020013 - No. 115, p. 2.

15 CIHI (2020), Pandemic Experience in the Long-Term Care Sector How Does Canada Compare With Other Countries?

16 Ontario Hospital Association (2019), Ontario Hospitals – Leaders in Efficiency.

17 Pat Armstrong, et.al. (2020), Re-imagining Long-term Residential Care in the COVID-19 Crisis. Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

19 Roberto Rocha, et.al. (2020), “Montreal’s poorest and most racially-diverse neighbourhoods hit hardest by COVID-19, data analysis shows,” CBC News.

20 City of Toronto (2020), COVID-19 infection in Toronto: Ethno-racial identity and income.

21 City of Toronto (2020), COVID-19 and the social determinants of health: What do we know?

22 Jennifer Yang, et.al. (2020), “Toronto’s COVID-19 divide: The city’s northwest corner has been ‘failed by the system’,” Toronto Star.

23 Kate Allen, et.al. (2020), “Lockdown worked for the rich, but not for the poor: The untold story of how COVID-19 spread across Toronto, in 7 graphics,” Toronto Star.

24 Finance Canada (2020), Economic and fiscal snapshot 2020.

25 David Macdonald (2020), The unequal burden of COVID-19 joblessness, Behind the Numbers, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

26 Statistics Canada (2020), “Labour Force Survey, April 2020,” The Daily.

27 Katherine Scott, et.al. (2020), Resetting Normal: Women, Decent Work and Canada’s Fractured Care Economy.

28 According to the 2016 Census, 80% of immigrants who came to Canada between 2006 and 2016 were from a visible minority group. Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population, Statistics Canada Catalogue no. 98-400-X2016191.

29 Statistics Canada (2020), “Labour Force Survey, April 2020,” The Daily.

30 Katherine Scott, et.al. (2020), Resetting Normal.

31 Jim Stanford (2020), “Encouraging job numbers but a long way to recovery,” Rabble.ca

32 Statistics Canada (2020), “Labour Force Survey, July 2020,” The Daily.

33 Ibid.

34 Ibid. Not adjusted for seasonality.

35 Ibid. Not adjusted for seasonality.

36 Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01 - Labour force characteristics, monthly, seasonally adjusted.

37 Ibid.

38 These employment figures includes those are employed at work as well as those who are absent from work. This group also includes many who will have taken leave to take care of their health, to care for others or to home school. Figures not seasonally adjusted.

39 Statistics Canada, Table 14-10-0287-01.

40 Dawn Desjardins, Andrew Agopsowicz, Carrie Freestone (2020), “The Fruits of her Labour: Canadian Women Are Reaping the Rewards of Their Labour-market Gains,” RBC Economics, March 2020.

41 For those who qualify for Employment Insurance, the majority (56%) will experience an average drop in support of almost $200 a week. And over 2 million people, currently ineligible for EI, will be cut off with nothing. David Macdonald (2020), What’s at stake in the move from CERB to EI, Behind the Numbers, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

42 Government of Canada (2020), Supporting Canadians through the next phase of the economy re-opening: Increased access to EI and recovery benefits. Backgrounder.

43 Dawn Desjardins, Carrie Freestone, Naomi Powell (2020), “Pandemic threatens decades of women’s labour force gains,” RBC Economic, July 2020.

44 ESDC (2020), Government of Canada announces funding to support organizations accelerating action on the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development in Canada. News Release, May 20, 2020.

45 Women’s Budget Group (2016), “Investing in the Care economy to boost employment and gender equality.”

46 Working Group on Long-Term Care (2020), Restoring Trust: COVID-19 and the future of long-term care, Royal Society of Canada.

47 Marco Chown Ovid, et.al. (2020), “For-profit nursing homes have four times as many COVID-19 deaths as city-run homes, Star analysis finds,” Toronto Star.

48 Faiza Amin (2020), Domestic violence calls surge during the coronavirus pandemic, CityNews.

49 Ontario Coalition of Rape Crisis Centres (2020), COVID-19, Pandemics and Gender: OCRCC Statement.

50 The Market Basket Measure, Canada’s new official poverty line, has been used to calculate these figures.

51 The targets have been criticized for lacking ambition. Indeed, the target for 2020 – to reduce the low income rate by 20% against the 2015 baseline – was achieved nine months prior to the announcement. See: Government of Canada (2018), Opportunity for All: Canada’s First Poverty Reduction Strategy.

52 For a summary of federal actions, see: Canada’s COVID-19 economic response plan.

53 With the exception of British Columbia, provincial and territorial governments did not enhance their own income security programs to assist low income residents and focused largely on strengthening health care systems and community services. Much of the support for this programming was flowed from the federal government for specific services such as education, public health, the purchase of PPE, etc. Three territories and provinces are fully exempting the CERB from the calculation of social assistance payments for recipients with earned income, resulting in higher incomes for those who have lost employment. Six others are treating CERB as unearned income and reducing social assistance benefits dollar for dollar.

54 For a detailed discussion of these proposals and others, please see: Canadian Centre for Policy Alternative (2020), New Decade, New Deal: Alternative Federal Budget, 2020.

55 In sharp contrast, EI paid an average $453 weekly before taxes (2018), with many people receiving much less than $400. CERB paid a flat $500 weekly before taxes. A new $400 minimum income rate has been proposed for the program.

56 UN Human Rights Council (2018), Report of the Working Group on the Universal Periodic Review: Canada. July 11, 2018.

57 Statistics Canada, 2016 Census of Population. Catalogue Number 98-400-X2016164.

58 Government of Canada, Ending long term drinking water advisories: website.

59 Jamil Malakieh (2018), Adult and youth correctional statistics in Canada, 2016/2017, Statistics Canada, Juristat, Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

60 Jillian Boyce (2016), Victimization of Aboriginal people in Canada, 2014. Statistics Canada, Juristat, Catalogue no. 85-002-X.

61 National Inquiry into Missing and Murdered Indigenous Women and Girls (2019), Reclaiming Power and Place: Final Report.

62 Truth and Reconciliation Commission of Canada (2015), Honouring the Truth and Reconciling the Future.

63 Department of Finance Canada (2020), Economic and Fiscal Snapshot 2020.

64 Finance Canada (2019), Fiscal Reference Tables.

65 CCPA (2020), New Decade, New Deal, p. 35.

66 In July, the average interest rate on five- and 10-year bonds was 0.39%, compared to about 9%, or 20 times higher, in the 1990s. Statistics Canada, Table 10-10-0122-01, Financial market statistics.

67 For a discussion of specific proposals, see CCPA (2020), “Tax fairness,”Alternative Federal Budget Recovery Plan, Canadian Centre for Policy Alternatives.

68 Auditor General of Canada (2019), Report 3 – Taxation of E-Commerce, Spring Reports of Auditor General of Canada.