Corporations, Investment Decisions and Human Rights Regulatory Frameworks

Published on Fri, 2017-05-26 13:52

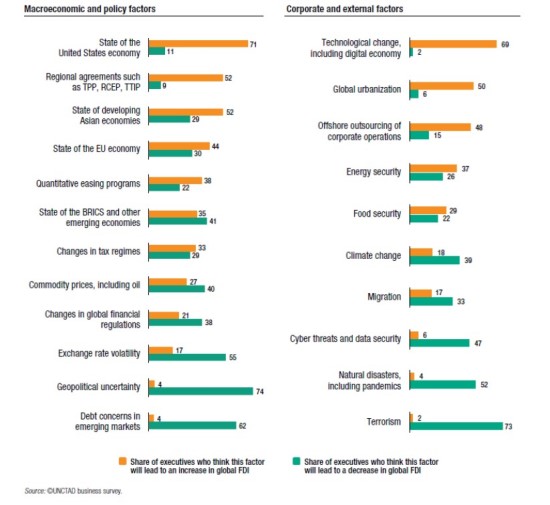

The question pertaining to the impact of States’ participation in designing an Instrument on transnational corporations and other business enterprises in the area of human rights (hereafter referred to as ‘the Instrument’) on attracting foreign direct investment has been a persistent issue of discussion since the mandate of the intergovernmental group on the Instrument was established. This mandate was established by Resolution A/ HRC/26/9 of the United Nations Human Rights Council, which was passed in July 2014. It is important to contextualize this question within an understanding of the role of investment policy as one of the development and economic policy tools available to States, including the role of both domestic and foreign investments, and within an understanding of the underlying determinants of foreign direct investment. This discussion could be informed by the experience of countries reforming their positions towards investment treaties, which entail a regulatory change pertaining to foreign investors. At the outset, it is important to underline that the discussions undertaken in regard to the Instrument thus far1 underscore that the objective of a prospective Instrument is not to adversely affect the business sector, but rather it is intended as a tool for clarifying clear and universal norms for the protection and promotion of human rights in regard to operations of transnational corporations and other business enterprises2. Thus, it would be an Instrument that focuses on addressing corporate violations of human rights, which is supposed to be an exception in corporate conduct, and not to over-regulate the corporate conduct in general. The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) points out that although many “multi-national enterprises (MNEs) demonstrate a respect for high standards of business conduct, some may neglect the appropriate principles and standards of conduct in an attempt to gain undue competitive advantage”3 (MNEs and transnational corporations (TNCs) are used interchangeably in this brief). This may be particularly true in environments where regulatory, legal, and institutional frameworks are underdeveloped or fragile. The main discussion entailed in the process towards a prospective Instrument does not pertain to making regulations more stringent, but to making regulatory frameworks clearer and more certain in different jurisdictions. Determinants of foreign direct investment (FDI) Empirical research does not point to regulatory frameworks as the primary determinants of FDI flows. A study published by the World Bank points out that business opportunities—as represented by the size and growth potential of markets—are by far the most powerful determinants of FDI4. It specifies that “for developing and transition economies, perhaps more important than market size is market potential growth”. After size and growth potential, other factors come into play, including proximity to markets and customers, investment climate, availability of skilled workforce, presence of partners or suppliers, infrastructure, among other factors5. In regard to ‘investment climate’, the report points to business regulations and government support. The report also discusses ‘strong institutions’ and the ‘quality of laws and regulations’. Thus, ‘investment climate’ does not stand for lack of regulations, but entails the quality and clarity of the regulatory frameworks. Decisions by corporations about their foreign investments are a complex multi-layered process that cannot be clearly associated with a specific factor. Indeed, there are multiple factors that play out in decisions pertaining to FDI (See Graph 1). Overall, there is a strong consensus in the literature that multinational corporations invest in specific locations mainly because of strong economic fundamentals in the host countries like availability of infrastructure, stable macro-economic environment and favorable policies6. Graph 1. Factors Influencing Future Global FDI Activity (showing percent of all executives surveyed by UNCTAD)

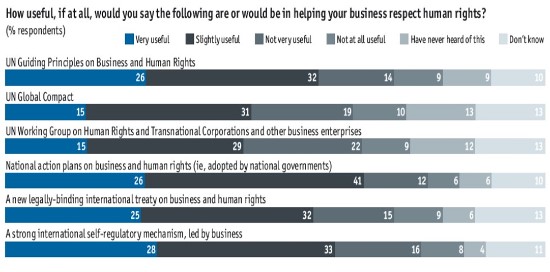

Furthermore, it is important to consider in this discussion the nature of FDI under consideration, which clarifies the incentives driving the FDI flows and enables a better reading in the aggregate data available in regard to the FDI flows. Akyuz points out that “contrary to widespread perception, direct investors are not always TNCs. It could also be an individual or household, an investment fund, a government or an international organization…readily available official statistics do not allow identifying them. This is one of the drawbacks of empirical studies linking aggregate FDI to various economic performance indicators in host countries…”7. Some experts point out that the notion that FDI is functionally indistinguishable from fresh capital inflows and represents a flow of foreign resources crossing the borders of two countries has no validity given that total recorded FDI includes, as an important component, retained earnings by investors8. Every financial transaction after the initial acquisition of equity by the investor, that is internal capital flows within the firm, are also considered direct investment9. Thus, the aggregate trends documented for increase or decrease in FDI do not give a full picture of the real value addition created in host countries, and do not allow for an adequate analysis of incentives behind the corporate decisions. Before basing broad policy positions, such as positions pertaining to human rights instruments, on trends in FDI flows, it is important to deconstruct the findings related to aggregate FDI flows and to try to understand the drivers of change in subcomponents of recorded FDI. Moreover, it is clear that TNCs thrive in highly regulated and litigious environments such as the European Union Member States and the United States. Indeed, standards for criminal, civil, and administrative liability are mostly well developed in these jurisdictions. Moreover, most of the litigation cases against corporations have been brought in these jurisdictions. Thus, the claim that improvement in the area of clarifying and enforcing standards will lead to hamper TNCs’ commercial activities does not stand on solid grounds. Accordingly, countries are not advised to decide their position vis-à-vis the discussions of a prospective Instrument with a presupposition that these negotiations would potentially leave a negative impact on FDI inflows. Lessons learned from the experience of reforming investment treaties Foreign investors are offered protections via a web of international investment protection treaties, which currently amount to more than 3,200 agreements (bilateral investment treaties (BITs) and free trade agreements with investment provisions)10, and offer foreign investors broad standards of protections. These treaties have been criticized as imbalanced, focusing on investors’ rights and neglecting investors’ responsibilities, and constraining the host states’ right to regulate in the public interest. Countries that attempted to redress the proven imbalance in the investment treaty regime, including investment treaties and investor-state dispute settlement mechanism, have been faced by severe scrutiny by proponents of the status quo. However, the experiences of reforming countries show that even in the period following withdrawal from international investment treaties or revision of their commitments under these treaties, they maintained their positions as growing markets attracting foreign investments. For example, South Africa commenced in terminating BITs after a cabinet review of these treaties undertaken in 2009. In the following period, South Africa remained a top receiver of FDI on the African continent; it was ranked by the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) as the top recipient of FDI inflows among the African countries in 201311. In 2006, Bolivia started to systematically withdraw from every BIT that reached its expiration date12. In May 2013, Bolivia collectively denounced all its remaining BITs. Concurrently, FDI inflows into Bolivia steadily increased in the following years, reaching an unprecedented peak of US$1.75 billion in 2013. For a long time, Brazil had no investment treaties ratified (in 2015, Brazil commenced negotiating and signing investment treaties based on a new model it enacted entitled “Agreement for Cooperation and Investment Facilitation model”13). During that period, Brazil remained one of the highest receivers of FDI, and was ranked as the 5th largest recipient of FDI in the world in 201314. Furthermore, empirical evidence from surveys of investors and political risk insurers have shown that it is exceedingly rare for foreign investors to factor in investment treaties (including liberalization agreements) when committing capital abroad, including deciding on the destination and volume of their investments. Similarly, availability and pricing of public and private political risk insurance is very rarely affected by the presence or absence of an investment treaty15. UNCTAD16 points out that over the years, numerous empirical studies have assessed the impact of international investment agreements (IIAs), including BITs, on foreign direct investment (FDI), resulting in mixed conclusions. UNCTAD points out that existing empirical studies of IIAs’ impact on FDI provide heterogeneous results and have some limitations because of data and methodological challenges, among other factors. More importantly, the study points out that “prominent counterfactuals (i.e. investment relationships that exist without being covered by IIAs) suggest that legal instruments’ influence on economic matters are limited and that other determinants, in particular the economic ones, are more important”. Further views from the corporate sector Empirical evidence points out that “transnational corporations seek regimes that respect human rights”17. For example, a study examining FDI inflows to all non-OECD countries during the period 1980-2003 found that countries that respect human rights receive higher FDI inflows. Another major study on labor standards and FDI points out that there is no evidence that FDI moves to countries with the weakest labor regulations; to the contrary the study notes that low labor standards seem to decrease FDI18. This is explained in part by the reputational risks associated with investing in countries that do not respect human rights. Another study focusing on European transnational corporations found that these enterprises value regulatory certainty when making location decisions, and are more likely to enter foreign countries with more stringent environmental regulations than those with lax regulatory environments19. The authors explain that finding by pointing out that these enterprises are accustomed to operate under strict environmental regulatory regimes. In 2015, the Economist Intelligence Unit (EIU) released a report entitled “The Road From Principles to Practice: Today’s Challenges for Business in Respecting Human Rights”, in which it asked senior corporate executives how ‘useful, if at all, would a new legally-binding international treaty on business and human rights be in helping their business respect human rights’20. The study was commissioned by the Universal Rights Group, together with DLA Piper, Eli Lilly, Global Business Initiative on Human Rights, Mazars and Telenor, among other parties. The results of the study were found to be “surprising, showing strong support for the claim that business needs to take human rights seriously”21. It was observed that “a large majority of executives now believe that business is an important player in respecting human rights, and that what their companies do—or fail to do—affects those rights”22. In the EIU survey, 83% of respondents agree (74% of whom do so strongly) that human rights are a concern for business as well as governments. Similarly, 71% say that their company’s responsibility to respect these rights goes beyond simple obedience to local laws23. Furthermore, it is telling that “when asked about the main barriers that their companies face in addressing human rights, only 15% of respondents agreed with the statement, “business would incur costs/see profit margins reduced”24. On the question pertaining to the usefulness of a legally-binding international treaty on business and human rights, the study’s results show that among the respondents, 25% thought it would be “very useful” and 32% thought it would be “slightly useful”, compared to 15% who thought that it would “not be very useful” and 9% who thought it would be “not at all useful” (See: Graph 2). Graph 2. Results of the survey conducted by the Economist Intelligence Unit

Concluding remarks The review presented by this brief describes a world where traditional perceptions of corporations, their investment decisions and its interface with human rights frameworks have significantly evolved and changed. Corporations are generally not averse to responsibilities in the field of human rights. Moreover, corporate decisions in regard to allocating investments is not pegged to actions that States take regarding regulatory frameworks, such as investment agreements or human rights regulations. Decisions by corporations about their foreign investments are a complex multi-layered process that cannot be clearly associated with a specific factor, but have been primarily associated with strong economic fundamentals in the host countries. Today, transnational corporations are entities of significant influence, and have been an active ‘actor’ in shaping the evolution of the law. Over the last few decades, a series of hard rules pertaining to corporate interests have evolved through the web of international investment treaties, rules pertaining to investor-state dispute settlement and related international enforcement rules25. Opponents of new rules pertaining to business and human rights never explain why hard rules are necessary to protect multinational corporations from potential misconduct by States, while soft rules are sufficient to protect people from the cases of misconduct by multinational corporations26. Corporations upholding human rights and investing in best practices across contractual and production chains ought to have a clear interest in movement towards developing a binding Instrument in regard to transnational corporations, and other business enterprises in the area of human rights. An Instrument at the global level will help avoid illegitimate corporate competition that could be achieved through exploiting differences in the applied standards and in mechanisms available to uphold the implementation of rights. More importantly, an Instrument at the global level will help level the playing field across jurisdictions, bringing more clarity to corporations in regard to the context they conduct their operations within and more certainty for victims of corporate abuse in regard to access to remedy. This will bring more certainty and consistency for all stakeholders. Notes: 1 To review a record of the initial session of the working group on an international legally binding instrument on transnational corporations and other business enterprises in the area of human rights, see: South Centre South Bulletin Issues 87-88 entitled “Business and Human Rights: Commencing discussions on a legally binding instrument”, available at: https://www.southcentre.int/south-bulletin-87-88-23-november-2015/.

2 See: Statement by Ambassador Maria Fernanda Espinosa, Chairperson-rapporteur of the working group on the Instrument, and Permanent Representative of Ecuador to the UN and other International Organizations in Geneva, which can be found in: South Centre South Bulletin Issues 87-88 entitled “Business and Human Rights: Commencing discussions on a legally binding instrument”, available at: https://www.southcentre.int/south-bulletin-87-88-23-november-2015/. 3 See: “OECD Guidelines for Multinational Enterprises: Responsible Business Conduct Matters”, available at https://mneguidelines.oecd.org/MNEguidelines_RBCmatters.pdf (visited 6.10.2016). 4 Kusi Hornberger, Joseph Battat, and Peter Kusek, “Attracting FDI; How Much Does Investment Climate Matter?”, published as World Bank Group View Point: Public Policy for the Private Sector (2011), available at: http://siteresources.worldbank.org/FINANCIALSECTOR/Resources/327-Attracting-FDI.pdf. 7 Yilmaz Akyuz, “Foreign Direct Investment, Investment Agreements and Economic Development: Myths and Realities”, South Centre Research Paper (2015), page 13, available at: https://www.southcentre.int/research-paper-63-october-2015/. 8 Ibid, page 14, referencing Veron 1999. 9 Ibid. 11 See: UNCTAD Global Investment Trends Monitor, January 2014 12 CEPALSTAT. (2014). Bolivia (Plurinational State of): National Economic Profile. Retrieved from http://interwp.cepal.org/cepalstat/WEB_cepalstat/Perfil_nacion al_economico. asp?Pais=BOL&idioma=i, referenced in “Risky Business or Risky Politics: What Explains Investor-State Disputes?” by Zoe Phillips Williams, Investment Treaty News, available at: https://www.iisd.org/sites/default/files/publications/iisd_itn_ august_2014_en.pdf. 13 Previously, Brazil had negotiated 14 BITs, however these agreements were not approved and ratified by its Congress due to the imbalance of the agreements and their impact on the state’s right to regulate. 14 Source: UNCTAD excluding the estimate for British Virgin Islands. 15 See: Lauge Poulsen, “The Importance of BITs for Foreign Direct Investment and Political Risk Insurance: Revisiting the Evidence”. In Yearbook on International Investment Law & Policy 2009/2010 (New York: Oxford University Press); Jason Yackee, “Do Bilateral Investment Treaties Promote Foreign Direct Investment: Some Hints from Alternative Evidence”, Virginia Journal of International Law 51:397 (2010-2011). 16 UNCTAD IIA Issues Note (Sept. 2014) “The Impact of International Investment Agreements on Foreign Direct Investment: An Overview of Empirical Studies 1998-2014”. Full note available at: http://investmentpolicyhub.unctad.org/Upload/Documents/unctad-web-diae-pcb-2014-Sep%2024.pdf. 17 “The Effects of International Business and Human Rights Standards on Investment Trends and Economic Growth”, by Cassandra Melton , business and human rights legal researcher, published by the Business and Human Rights Research Centre, available at: https://business-human-rights.org/sites/default/files/media/documents/the_effect_of_business, referencing S. Blanton and R. Blanton. “Human Rights and Foreign Direct Investment: A Two-Stage Analysis”, Business and Society, Vol. 45, No. 4 (2006). The authors in this study found that countries that respect human rights receive higher FDI flows. The abstract of the paper points out that “Although the “conventional wisdom” posits that repression creates a stable, compliant, and relatively inexpensive host for FDI, there are contending arguments that the protection of human rights reduces risk and contributes toward economic efficiency and effectiveness. Moreover, the burgeoning “spotlight” regime may also punish firms who locate in repressive regimes”. Available at: http://bas.sagepub.com/content/45/4/464.abstract. 18 David Kucera (2001), “The Effects of Core Workers Rights on Labor Costs and Foreign Direct Investment: “Evaluating the conventional wisdom”, International Institute for Labour Studies, referenced in Cassandra Melton, “The Effects of International Business and Human Rights Standards on Investment Trends and Economic Growth”. 19 Rivera and Chang (2013), “Environmental Regulations and Multinational Corporations’ Foreign Market Entry Decisions.” Policy Studies Journal, Vol. 41, No. 2. The study examines the first-time foreign subsidiary location decisions of 94 European Union multinationals between 2001 and 2007. The study is referenced in “The Effects of International Business and Human Rights Standards on Investment Trends and Economic Growth”, by Cassandra Melton. 20 The report is based on an online survey of 853 senior corporate executives carried out in November and December 2014, and indepth interviews with independent experts and senior executives of major companies. 21 See: “Mapping global business opinions on human rights”, by Marc Limon (August 8, 2016), available at: 22 Ibid. 23 Ibid. 24 Ibid. 25 See for example: the New York Convention on the Recognition and Enforcement of Foreign Arbitral Awards (1958), available at: http://www.uncitral.org/uncitral/en/uncitral_texts/arbitration/NYConvention_status.html. 26 Developing Countries in the Investment Treaty System: A Law for Need or a Law for Greed? by M. Sornarajah (2016). By Kinda Mohamadieh. Research Associate, the South Centre. Download here the pdf version. Source: The South Centre. » |

SUSCRIBE TO OUR NEWSLETTER