Lower Oil Revenues, Higher Public Debt: The Implications of Low Oil Prices and Challenging Financing for Sustainable Development

Kenan Aslanli

Public Finance Monitoring Center (PFMC)

This article examines fiscal policy and the main parameters of Azerbaijan’s fiscal position in the context of the severe constraints (namely, reduced budget revenues and cuts in government spending) posed by the decline in crude oil prices. These constraints can also hamper the financing of sustainable development initiatives. Azerbaijan’s fiscal balances have deteriorated considerably as crude oil prices have tumbled. A worsening of the country’s fiscal balance could gradually contribute to an increase in the public debt burden and threaten fiscal sustainability in the long term. Azerbaijan’s sovereign wealth fund, SOFAZ, now has very limited profits from the sale of oil, and will contribute less to the fiscal revenues of the state as a consequence. The national state-owned oil-gas company, SOCAR, temporarily cancelled its plans for a new oil-gas refining and petrochemical complex because of the rapid fall in crude oil prices. However, at the same time, the new low oil price environment also offers an opportunity to boost a new wave of fiscal and public administration reforms in Azerbaijan.

Fiscal implications of lower crude oil prices

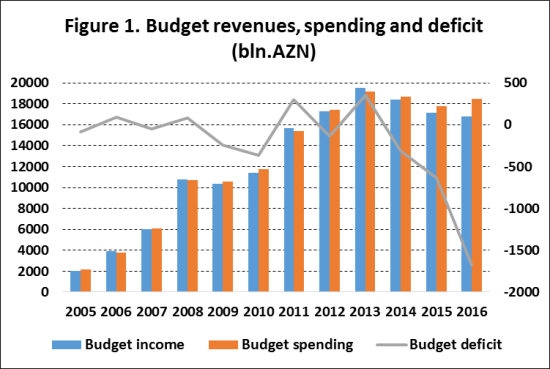

The drop in oil prices and resultant waves of devaluation hit Azerbaijan’s economy and fiscal balance especially hard by diminishing oil revenue inflows to the fiscal system and decreasing budget incomes. Oil, gas and mineral revenues account for more than 77 percent of Azerbaijani budget revenue for 2014,1 and low oil prices affected almost every aspect of the country’s fiscal policy. Fiscal policy adjustments made in response to the new reality include changes in government budget revenues; changes in the structure of government budget spending, including cuts to capital and recurrent expenditures; new sources of financing for the budget deficit; changes in the assets of the State Oil Fund (SOFAZ); and changes in the operations of the State Oil Company (SOCAR). Both revenue and spending aspects of fiscal policy have encountered severe constraints due to low oil prices, namely the shortfall in budget revenues and cuts in government spending. Current fiscal balances have deteriorated amid plunging oil prices.

Decreased crude oil and natural gas production coupled with lower crude oil prices led to a contraction of the country’s GDP in 2015 (economic growth was measured at 1.1%, down from 2.8% in 2014). Additionally, the poorly diversified Azerbaijani economy has been particularly vulnerable to the oil-price shock because of its higher fiscal dependence on revenues from hydrocarbon exports. The Government has decided to reduce the budget for public investment by 40 percent from 2015 to 2016 and to halt the financing of new investment projects. Total revenues of the consolidated budget decreased 6 percent as a result of oil price readjustments (from US$50 per barrel to US$25 per barrel in the revised budget for 2016) and falling revenues from the national sovereign wealth fund (SOFAZ), which has traditionally played a central role in the country’s fiscal policy.

|

Sources: Author’s calculations based on data from the Azerbaijan Republic Ministry of Finance and Budget.

The declining fiscal balance (Figure 1) will gradually contribute to an increase in the public debt burden, thus threatening the country’s fiscal sustainability: Azerbaijan’s debt-to-GDP ratio is 19.8 percent (as of January 2016). The Government introduced new tax rates for simplified and income taxes as concessions to local entrepreneurs, without any serious changes in the rates of central taxes such as the VAT or the corporate profit tax. In addition to deepening our analysis of the above-mentioned “unexplored” fiscal trends, we need to investigate the fiscal consequences of constrictions on SOCAR’s receipts from crude oil sales as well as subsidies to state-owned companies and natural monopolies. Beyond the immediate fiscal consequences, such as budget cuts from both the revenue and expenditure sides, public asset sales, and tax rate changes, the commodity price bust is influencing medium and long-term fiscal plans.

Fewer transfers from SOFAZ led to contraction in actual state budget revenues

Low oil prices in international markets had an immediate adverse impact on implementing the national budget: budget revenues for the end of 2015 fell by 11.8 percent and state expenditures dropped by 15.7 percent compared to figures approved in the previous year’s state budget. The incomes of the state budget were executed for 17.153 billion manats instead of the approved amount of 19.438 billion manats, or 11.8 percent less, in 2015.

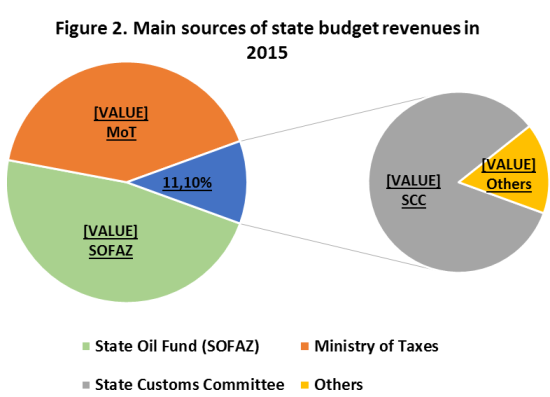

These figures indicate that actual total budget revenue figures are falling behind initial forecasts. First, SOFAZ was the primary source of budget revenues, representing 47.4 percent of contributions (transfers) to total revenues. These transfers were 21.7 percent lower than the original approved forecasts. Second, taxes and other mandatory payments collected and transferred to the Ministry of Taxes accounted for 41.5 percent of state budget revenues. Income from the non-oil sector constitutes 70.5 percent of that amount, which is 16.5 percent more than in 2014. Third, the State Customs Committee generated 9.3 percent of total revenues, which was 5.4 percent more than the previous year in absolute terms.

|

Source: Azerbaijan Ministry of Finance; Budget.az; author’s calculations.

Finally, Figure 2 demonstrates that three institutions (SOFAZ, the Ministry of Taxes and the State Customs Committee) “carved out” the vast majority of fiscal revenues (98.2%), but the dominance of SOFAZ as a commodity-based extra-budgetary saving and stabilization fund jeopardizes fiscal sustainability in the long term. According to an independent budget review by a local think-tank, Support for Economic Initiatives, “the amount of transfers to the state budget from the State Oil Fund [has been] significantly reduced. The role of direct payments from the oil sector in the formation of state budget revenues has [been] considerably reduced in both absolute and relative terms.”2

SOFAZ will contribute less to the state budget revenues, in contrast to previous years

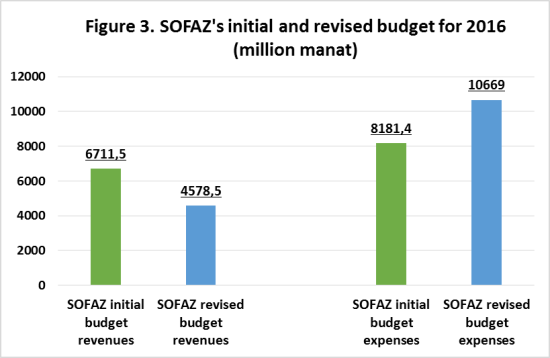

In addition to making amendments to the state budget, the government has also revised the SOFAZ budget for 2016, decreasing revenues and increasing expenses in proportion to the initial version of the SOFAZ budget for 2016 (Figure 3). The amended SOFAZ budget for 2016 envisions 4.6 billion manats in revenue and 10.7 billion manats in expenditures.3 More precisely, this is a significant decline in SOFAZ’s earnings and a sharp increase in SOFAZ’s expenditures compared to the budget implemented for 2015 or the initial version of the budget for 2016.

The majority of income for SOFAZ’s 2016 budget will come from the sale of profit oil. Table 1 shows that while the main budget expenditure line of SOFAZ for 2016 denoted transfers to the state budget, it will contribute less than that amount to fiscal revenues (http://www.oilfund.az).

|

Source: Azerbaijan Republic Ministry of Finance; Budget.az; author’s calculations

Despite financial difficulties, SOFAZ will continue to finance national and regional infrastructure projects such as the Baku-Tbilisi-Kars railway project, Azerbaijan’s share in the Southern Gas Corridor project, the reconstruction of the Samur-Absheron irrigation system and the construction of the “STAR” Oil Refinery in Turkey.

Table 1. SOFAZ’s budget transfers (2003-2016, million AZN)

|

Years |

Fiscal revenues from SOFAZ (transfers) |

Share of SOFAZ budget transfers in total budget revenues, % |

Share of SOFAZ budget transfers in GDP, % |

|

|

2003 |

100.0 |

8.2 |

1.3 |

|

|

2004 |

130.0 |

8.8 |

1.5 |

|

|

2005 |

150.0 |

7.2 |

1.2 |

|

|

2006 |

585.0 |

15.1 |

3.2 |

|

|

2007 |

585.0 |

9.7 |

2.1 |

|

|

2008 |

3800.0 |

35.3 |

9.5 |

|

|

2009 |

4915.0 |

47.6 |

14.2 |

|

|

2010 |

5915.0 |

51.9 |

14.2 |

|

|

2011 |

9000.0 |

57.3 |

18.0 |

|

|

2012 |

9905.0 |

57.3 |

18.3 |

|

|

2013 |

11350.0 |

58.2 |

19.7 |

|

|

2014 |

9337.0 |

50.7 |

15.8 |

|

|

2015 |

8130.0 |

47.6 |

14.2 |

|

|

2016 (projected) |

7615.0 |

45.3 |

12.6 |

|

Source: Budget.az.

One of the implications of recent low oil prices and currency devaluation for fiscal policy was the appearance of SOFAZ as a seller at the foreign exchange auction of the Central Bank (CBA). SOFAZ has stated that it will continue selling currency through CBA auctions. There is no legal rule that regulates SOFAZ’s presence at the foreign exchange auctions or its direct transfers to the state budget. It is evident that when oil production begins to decline or global oil prices drop, the Government will be forced either to run a budget deficit or to draw more funds from SOFAZ. These options are unsustainable in the long term and could lead to a debt crisis, which would result in high costs and a lower standard of living for future generations; a debt crisis could also return Azerbaijan to levels of development and poverty that preceded the discovery of oil. In addition to borrowing and drawing money from SOFAZ, a third option would be to raise tax revenues from the non-oil sector. However, to this date, this has proven difficult because non-state non-oil growth remains weak and non-oil tax revenues linger steadily at approximately 20 percent of GDP, much lower than the 30-45 percent level in most developed countries.4 However, it is very unpopular to raise taxes and as a response people will seek to avoid them, hence the expected growth of the “shadow” economy.

Public investment programme has attracted less public money

State budget expenditures in 2015 were implemented at the level of 17.15 billion manats instead of the forecasted 21.1 billion manats, representing a decrease of 15.7 percent. Current expenditures (58.2% of total expenses) were more than capital expenditures (37.8%) in 2015. Four percent of all expenditures were allocated to finance related costs for the maintenance of state debts and other commitments during 2015. The public investment programme accounted for 28.1 percent of state budget expenditures (33.4% in 2014). Azerbaijan’s state budget is socially oriented, and therefore, one-third of its total expenses were allocated to financing social expenses.

Government readjusted its fiscal parameters to new realities for 2016 state budget

The Government proposed new amendments to the state budget for 2016 and parliament approved these changes. The per-barrel crude oil price was set at US$25 in forecasts of revised state budget revenues in 2016. This change increased the income of the state budget by 15.5 percent and expenditures of the state budget by 13.7 percent in comparison with an initially adopted version of the budget (2% less than the implementation of the state budget for 2015).

There is a plan to secure additional revenues for the state budget through more transfers from SOFAZ (27% more in the revised budget than in the initial version) and more tax revenues from the non-oil sector of the economy. However, there is an alternative approach in which the significant increase in the special share of payments from the non-oil sector contributing to state budget revenues is mainly due to decreases in total budget income and in the absolute amount of oil revenues in the budget. Short of state oil fund transfers, state budget revenues will not be able to adequately finance current annual expenses. Substantial cuts to the public investment programme for next year have applied also to socially oriented areas such as education and health. In other words, the Azerbaijan Government has adjusted fiscal policy to the falling oil prices and oil revenues. Public investment has been relatively lowered, but targeted social assistance has been raised.

Budget deficit raised total debt burden

After the rapid decline of crude oil prices and after experiencing a relatively high budget deficit, the Ministry of Finance decided to hold regular auctions of state bonds by registered emission prospectus for an amount totaling US$500 million until the end of 2016.5 For the year 2015, government indebtedness stands at just over 12 percent of GDP. During that period, the country accumulated substantial foreign currency reserves of approximately US$39 billion (73% of GDP, although these reserves then decreased to US$33.5 billion), which provided a sufficient guarantee against any possible adverse external and internal shocks. However, the situation deteriorated in 2016.

Public debt will increase in 2016, reaching 50.5 percent of budget revenues and 46 percent of budget expenditures. Furthermore, Azerbaijan’s tax debt is estimated at AZN 2.4 billion. The budget burden for payment of the national debt increased considerably in 2015 and 2016. “Ricardian equivalence” theory assumes that when the government attempts to stimulate demand by increasing debt-financed government spending, demand can remain unchanged; this is because the public will retain its savings to pay for possible future tax increases that will be applied to paying off the debt burden.6 This has two implications: (a) debt burden increases make citizens more cautious about consumption; (b) public debt will be replaced by a tax burden on the population in the long run.

National oil company encountered serious challenges in financing new projects

State-owned oil companies such as SOCAR find themselves with fewer financial resources to spend on costly upstream or downstream projects. SOCAR is the key player in Azerbaijan’s energy sector, but it does not transfer its total oil revenues to the state budget. In 2015, SOCAR paid 1.48 billion manats to the state budget, which was 20 percent less than the previous year (SOCAR’s total revenue figures for 2015 are not available to compare budget transfers with revenues). Moreover, the company directly finances some energy-related (and in some cases, even non-energy related) projects. Due to low oil prices, SOCAR decreased crude oil and natural gas production in 2015 and suspended some new projects. It announced the termination of its project on a new oil-gas refining and petrochemical complex. National or state-owned oil-gas companies such as SOCAR seem insufficiently prepared to lower oil price conditions considering the importance of cost effectiveness, efficiency maximization, and their fiscal roles as taxpayers. As in the case of SOFAZ, there are no rules to regulate the portion of revenue that must be transferred or invested by SOCAR. After lower crude oil prices, SOCAR didn’t cancel any planned major projects, including the modernization of existing main refinery in Baku. But the company had borrowed 1.86 billion manat from the International Bank of Azerbaijan with a state guarantee by the Ministry of Finance.7

Some fiscal policy-related reforms amplified during the crisis

As part of a series of institutional changes, President Ilham Aliyev established a new position and appointed the former deputy tax minister as his economic reforms assistant. Azerbaijan began to introduce a BOT (Build-Operate-Transfer) model for construction and infrastructure projects to attract alternative financing sources. The Government also exempted investors (investment certificate holders) from some taxes and customs duties (by up to 50% for 7 years) and prepared anti-dumping duties to prevent import growth. Due to the latest changes in the Tax Code, owners of retail service and catering service entities with an annual turnover of up to 200,000 manats will pay 6 percent and 8 percent simplified tax accordingly.

The fiscal crises made fiscal discipline an unavoidable component of possible reforms. But unfortunately the separate law on state financial control and a new Budget Code have not yet been prepared and adopted. Despite the fact that the Government has already developed a medium-term expenditure planning, it has not yet transformed the budgeting to the Medium-Term Expenditure Framework which enables it to track cyclical changes on the main fiscal parameters. SOFAZ as an extra-budgetary sovereign wealth fund and main donor of the state budget requires new regulations or a law depicting its saving and stabilization functions with clear deposit and withdrawal rules. The institutional capacity of the Government should be improved in order to enable it to adopt counter-cyclical fiscal policies and harmonize different components of the budget system (especially, interrelations between state budget and extra-budgetary funds).

Conclusion

Falling crude oil prices and consequent reductions in fiscal and budget revenues have amplified the Government’s budget deficit in Azerbaijan. The volatility of crude oil prices in the world market and the depletion of the country’s foreign exchange reserves have led to massive fluctuations in fiscal parameters. The Government is not in the sustainable fiscal position of having a low level of public debt. This is a predictable consequence of Azerbaijan’s high dependence on crude oil, which accounted for 77.6 percent of total exports and 60 percent of state budget revenues in 2015. Even if public debt is still relatively low as a percentage of GDP, lower oil revenues compared to previous years indicate that the country has reduced fiscal ability to pay down these debts. Accordingly, there is a need to adopt a new fiscal policy and fiscal rules based on medium-term budget expenditure planning, fiscal discipline and sensitivity analysis to create more fiscal surplus in order to meet long-term development commitments and to pay down public debt through SOFAZ, which accumulates fiscal surplus. However, at present, despite fiscal stabilization and the availability of SOFAZ as a savings instrument and a tool to finance sustainable development, the country still faces difficulties in fiscal policy. In Azerbaijan, there is no fiscal rule that limits annual spending of SOFAZ’s oil revenues.

Despite the fact that crude oil prices remained low for 2015, the government didn’t adopt tense fiscal decisions to cut spending or to raise tax rates. The government plans to contract public investment spending almost 40 percent in 2016 compare with 2015, but it also plans to raise social spending. As a result, total budget spending in 2016 has been planned to be 4 percent more than in 2016, notwithstanding, total budget revenues will be almost 2 percent lower in 2016 compare with 2015. Fiscal policy in Azerbaijan was expansionary and pro-cyclical policy over previous years thanks to high crude oil prices. Currently, the government attempts to adjust it fiscal policy to new realities characterized with lower oil prices and revenue volatility without damaging its social obligations and adopting contractionary fiscal policy.

As in other natural resource-rich countries, Azerbaijan has faced almost all the significant consequences of lower crude oil prices, including increased budget deficits and public borrowing, relatively lower capital investments from the budget, and cancellation of some projects by the national oil company. However, this new environment has also boosted a new wave of fiscal and public administration reforms. Azerbaijan scored 51 (on a 100-point scale) in budget transparency (Open Budget Index 2015) which is slightly higher than the global average indicator of 45.8 There is room for maneuvering here to enhance access to budget data and improve the quality of the budget cycle, including budget forecasting and more efficient medium-term fiscal policy planning. The government can increase the comprehensiveness of the executive’s budget proposal by adding more details to fiscal policy narratives and fiscal performance indicators.

Notes:

2 “Review of 2016 state budget (forecast) of Azerbaijan Republic,” Support to Economic Initiatives Public Union, 2005, http://budget.az/en/upload/files/SEI_Budget_Review_2016.pdf

3 SOFAZ 2016 budget approved, http://www.oilfund.az/en_US/hesabatlar-ve-statistika/buedce-melumatlari/azerbaycan-respublikasi-doevlet-neft-fondunun-2015-ci-il-buedcesi-tesdiq-edildi-2.asp#sthash.MQcFQTPO.dpuf

4 Kenan Aslanli, “Fiscal Sustainability and the State Oil Fund in Azerbaijan”, Journal of Eurasian Studies 6: 2 (2015): 114-121.

5 “The Ministry of Finance successfully issues state bonds”, 8 February 2016, http://www.maliyye.gov.az/en/node/1885

6 Robert J. Barro, “The Ricardian Approach to Budget Deficits,” Journal of Economic Perspectives, 3: 2 (1989): 37-54, http://faculty.georgetown.edu/mh5/class/econ102/readings/budget_deficits.pdf

8 Open Budget Survey: Azerbaijan, 2015, http://www.internationalbudget.org/wp-content/uploads/OBS2015-CS-Azerbaijan-English.pdf