Global Development Cooperation: Challenges and Opportunities

Theocharis Michail, Sotiris Themistokleous

CARDET

Cyprus has traditionally thought of itself as being a multicultural hub, situated, as it is, in the intersection of three major cultures: African, Middle Eastern and European. However, instead of the more nuanced and fluid identity required for the country to be a truly multicultural society, public and private discourses identity have existed in a perpetual feedback loop, reproducing rigid and highly localized narratives about Cypriot identity. In examining its potential to implement the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, this report identifies these narratives to include 1) the polarizing discourse concerning the relationship with Turkey and Greece; 2) the tension between public welfare spending, the power of labor unions and the advocates of free market neoliberalism and limited government; and 3) the conflict venting proxy of Cyprus football that is situated in the intersection of both the Cyprus national identity crisis and the public – market relationship.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development: An Ambitious New Vision

The Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) were one of the first attempts to set a global development agenda, focused on achieving a priority set of goals in a specific time frame and bringing together government and non-government institutional resources. While the outcomes of this agenda varied across countries, considerable gains were made in many countries, including Cyprus. Even more significantly, the MDGs seems to have contributed to giving the global public, a theoretical framework by which to understand larger globalization effects through the examination of trends on global challenges such as extreme poverty, the environment, gender equality, and access to education and health care.

The UN and its Member States have built on the experience and knowledge generated by the MDGs and through the democratization of the process of identifying the goals and targets, and have them apply to all countries, not just developing countries, have agreed on an agenda that is far more wide-reaching and honest about the inherent global challenges. Despite its arrival in the wake of the global financial crisis and economic recession, the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and its 17 sustainable development goals represent an ambitious vision of a collective future that could potentially counterbalance the narrow self-interested policies that these type of crises inevitably bring forward.

Cyprus narratives

Public discourse in Cyprus has traditionally thought of the country as being a multicultural hub, situated, as it is, in the intersection of three major cultures: African, Middle Eastern and European. However, this discourse has not been well equipped to adapt to the more nuanced and fluid identity that would be required by a truly multicultural society. The public and private discussion spheres have existed in a perpetual feedback loop, reproducing rigid and highly localized narratives.

The narratives fuelling the feedback loop are the following, ranked in terms of significance:

1. The so-called ‘Cyprus problem’, regarding the relationship with Turkey and Greece. Dominating both the public discourse and the private domain since the 1950s, it has become very socially and politically polarizing as attempts to resolve its political dimensions slowly force a discussion of the unresolved national identity crisis.

2. The tension between public welfare spending, the power of labor unions and the advocates of free market neoliberalism and limited government, particularly since the 2015 banking crisis in Cyprus.

3. The conflict venting proxy of Cyprus football that is situated in the intersection of both the Cyprus national identity crisis and the public–market relationship.

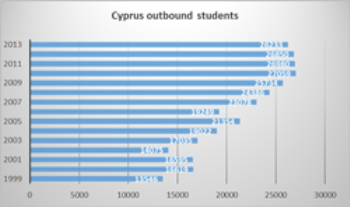

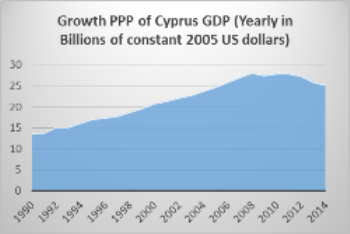

This feedback loop has been weakened in recent years (gradually since the 1980s and more quickly since EU integration) through increased economic prospects during the ascension in the EU membership, progressive European directives and law harmonization (see Figure 1) and greater labor mobility within Europe, resulting in an increasing number of university graduates going to the UK for further education (Figure 2). These changes provided fertile ground for a number of ideas to seep through the cracks of the very sclerotic and esoteric narrative of public and private Cyprus discourse. 1

Challenges to implementing the 2030 Agenda

There is a risk that the ongoing economic crisis and public focus on finding a workable national solution to Cyprus divide will dominate national policy-making, in both the public and private spheres and inhibit the development of a broader vision, thus further deprioritizing the Sustainable Development Goals. The Government needs to issue a pro-active statement adopting this agenda in as many public spheres (media, education, politics, civil society) as possible so that the momentum will not be lost.

A second threat to implementing the agenda is a long established inertia on the part of the Government with regard to non-binding agreements, owing in part to the lack of a track record in terms of active engagement. This problem is exacerbated by the fact that the public discourse, mediated by media outlets, focuses on the more comfortable domestic narrative, thereby reducing public pressure for any meaningful engagement by the state.

A good example of this was an initiative to update the law on Non-Government Organizations and Social and Solidarity Enterprises. Cyprus has not yet defined specific requirements and incentives that differentiate Social and Solidarity Companies and Organizations from For Profit companies which forces the Development Cooperation and Social & Solidarity Economy department to follow the legal framework of an outdated 1972 Societies and Institutions Law. This law does not reflect the development of not-for-profit companies and it is of limited guidance to the social entrepreneurs of today, striving to define the legality of their operations. Discussion over a new law has been in process since 2008 but no proposal has yet been introduced in the Parliament.2

A notable addition to the inertia regarding global engagement seems to be the corporate sector. By and large the market economy in Cyprus has been very adaptive to the newest productivity tools provided by the economic globalization but has impeded efforts to generate greater engagement on sustainability.

One of the problems is the lack of pressure by both the public and private spheres (with the exception of European directives) to engage in a discussion about the sustainability of the practices. A major issue is lack of incentives as the vast majority of the economy is supply oriented with limited exposure to production practices that would lead to a greater scrutiny. As a result, the main focus is limited to labor rights and not at all at the global supply chains discussion and the effects of the production in the local population and the environment. Additionally, there seems to be a clear divide in the collective consciousness in the corporate field about the pure profit making goal of companies in accordance with individualism ideals teamed with unfettered capitalism and the socially responsible (charitable) organizations. Even culturally passed down organizations, like the co-operative sector, have been re-invented as for profit organizations on the basis of rationalization.

Finally, while ideas of social enterprises are getting a foothold in specific segments of the market, the overwhelming majority of companies are not particularly aware or concerned with sustainability. Based on our understanding of the market we feel that the agenda 2030 will most likely be perceived with suspicion as it will be assumed that the ethical standards that would need to be adopted, like due diligence and minimization of carbon footprint etc., will increase their operational cost or lower the demand so it will be reasonable that the response will range from null to ostensibly opposed.

The Future of Engagement in both Public and Private Spheres

Despite these problems, there are a number of factors that might allow for a more positive read of the future.

Cypriot society (economy, culture) seems to be highly integrated into the global system that, while challenging, is making it increasingly difficult for the public sphere to engage into a conversation without any global analysis. This is exacerbated by the pressing needs that have arisen by the globalized framework of the economic crisis.

While this is true in the public sphere, the news from the private sphere are even more encouraging with internet penetration at 95 percent and Facebook subscribers at 69 percent of the population (highest in EU 28) 3 proving that the media sphere is expanding and is no longer absolutely captive to the public discourse feedback loop.

This exposure to dynamically entrepreneurial systems along with the decline of traditional industries has manifested itself in a cultural change in terms of traditional occupations and operations to incorporate new adaptive and innovative entrepreneurial spirit of the generation under age 40, has led to a sprout of innovative ideas with the creation of new innovative businesses and by adapting a new ethical operations methods directly borrowing from experiences in the west. After the turn of the millennium we are observing a modest growth of Social and Solidarity Enterprises in Cyprus perpetrated and addressed to this dynamic generation.

Existing companies are also seeing the benefit of adopting ethical principles as a marketing tool to differentiate their product in the highly competitive consumption sector in Cyprus. While these companies are adopting these principles in a pure profit making framework, the effect of doing so is creating a higher qualification floor for the consuming public and thus should probably be considered as a positive unintended consequence towards a more sustainable consumer.

These factors are supported by the newly established Development Cooperation sector in Cyprus which is facilitating a link between the grassroots community and the institutional stakeholders and aids in the change of mentality by running high profile European inspired and funded projects. This dynamic sector is creating the circumstances, resources and networks that could become the bedrock of a solid effort to establish global citizenship engagement which is pre-requisite for the adoption of the Sustainable Development Goals agenda Bottom-up and Top-down.

Cyprus public figures have been vocal about their commitment to the 2030 Agenda 4 and the narrative put forth is that there is the political will to adopt them and make a real impact. Particularly, important is the fact that the Ministry of Agriculture, Department of Environment has become the focal point for the Sustainable Development Goals 5 seems poised to assume that responsibility. However, there is no task force to manage interdepartmental coordination between ministries and jurisdictions, provide a coherent strategy for achieving the targets or declare whether efforts will be focused locally or internationally, organize consultations with the CSO community or even identify best practices for each ministry to follow as general principles. Instead this same ministry (Agriculture) has taken some hotly contested decisions about demarking part of national parks for tourism development, providing licenses for heavy industries in light industry areas close to communities, and assuming pro-industry positions through the EU Trialogue process on conflict-mineral legislation. The approach followed by Cyprus during the MDGs however limited in scope and definitely in scale did produce some results especially in terms of global citizenship education and awareness raising activities and limited Development cooperation aid (scholarships, military equipment, outsourcing funds to foreign aid agencies).

In terms of public responses to sustainable development challenges where these intersect with interests of special groups in the society the state is very responsive, either protecting the interests of the special interest group (land developers etc.) or in rare, generally highly publicized, cases adhering to the electorate’s pulse, especially in election years. This willingness to go either way betrays a lack of coherent framework throughout government departments while a process has not yet started.

We believe that this growing dynamism toward greater global engagement, in both the public and private sphere, has developed irrespective of the wishes of the higher echelons of the Government, which makes it a grassroots change untethered to the impulsiveness of public discourse.

There are a number of political recommendations that could provide an institutional framework towards implementing the 2030 Agenda in Cyprus.

1. A dedicated Sustainable Development Department. While adopting the SDG goals as a general policy framework for all Government departments is well intentioned it can become a recipe for dilution of vision despite sincere efforts by individual officers in various ministries. Although the SDGs are under the auspices of the Ministry of Agriculture the ministry has a very specific set of policy goals that do not reach the breadth of the goals as a whole, while collaboration between ministries is notoriously difficult and rife with jurisdictional power struggles. The SDGs would be much better served by an inter-ministerial and intra-departmental entity, preferably under the backing of the President. The best way to implement the SDGs would be for the Directorate General for European Programmes, Coordination and Development to adopt the SDG framework for all government programmes, starting at the design phase.

2. A law for social companies. A renewed push to get the law of the limbo it has been in since 2008 would require a coordinated and focused effort by the Government. The Directorate for European Programmes, Coordination and Development has initiated efforts to restart the conversation with the Civil Society Organizations in Cyprus to define Non-Government Organizations and Social & Solidarity Enterprises so that there will be a clear understanding of the distinctions, incentives and regulation needed for this novel type of organization. This will require constant jerking to surmount institutional inertias, but the benefits of a well-designed law will more than compensate the arduous journey. What is needed is a roadmap for this process so that clear deadlines will need to be met and not allow new process to run out of steam once again.

3. A dedicated budget. Finally, and most difficult, there is a need for a dedicated recurring budget line, however small, to be allocated to the goals of Agenda 2030. This budget would then force the government apparatus to distribute the resources, prioritize goals and create long-term strategies and short-term projects in a perverse ends satisfy means manner.

|

Fig 1. Total outbound internationally mobile tertiary students studying abroad, all countries, both sexes (number) – UNESCO

|

Fig 2. PPP GDP is gross domestic product converted to international dollars using purchasing power parity rates – EuroStats

Notes: