Growing social inequalities

Matyas Benyik

Social Watch Hungary

Demographic trends1

The population of Hungary was 10,588,614 on 1 January 1989; three decades later, on 1 January 2018, it was 9,778,371 – a difference of over 800,000. If we consider the number of births and deaths between the start of 1989 and the end of 2017, it becomes obvious that the underlying changes were even more fundamental. In 2017, there were more than 30,000 fewer births and about 13,000 fewer deaths than in 1989. In the whole period under consideration, close to a million more people died than were born; the only reason why the population did not decline accordingly was that net migration until 2010 was clearly positive (more immigration than emigration). However, net migration changed recently, and therefore today migration also contributes to population decline. Every third child is living in poverty in Hungary2. So many young Hungarians have left the country that every sixth Hungarian child is born abroad3. There is a secondary school where every third baccalaurate is going abroad.4

PM Viktor Orbán regains powerful majority

Hungary has been governed consecutively by Viktor Orbán and his Fidesz party since 2010. His first term was between 1998 and 2002. In the April 2014 parliamentary elections, Orbán was reelected after his right wing party won 48 percent of the vote, enough for two thirds majority in the Parliament despite receiving 600,000 fewer votes than in 2010, thereby demoralizing the opposition further. In the period between 2010-2018, the government continued its dismantling of checks and balances and its „re-feudalization” of the economy and society. Right after the elections the party composition of the House: the Federation of Young Democrats–Hungarian Civic Alliance and the Christian Democratic People's Party (Fidesz-KDNP) won 133 seats out of 199. The extreme right Movement for a Better Hungary (Jobbik) took 26 mandates, the election alliance of the Hungarian Socialist Party and the Dialogue Párbeszéd (MSZP-P) got 20, the former PM Ferenc Gyurcsány’s Democratic Coalition (DK) 9 and Politics Can Be Different (LMP) 8. Together (Együtt) and the ethnic German minority is represented by a single lawmaker each. An independent candidate has also won a seat. This means that in the newly elected Hungarian parliament 159 seats were taken by the far right (133 for Orbán’s Fidesz and 26 for the far-right Jobbik party in opposition).

The strong position of the fourth Orbán government means that democracy in Hungary will continue to erode, pervasive corruption will undermine both democracy and economic growth, societal polarization will continue, the rift between liberal Budapest and the more traditional countryside will grow, qualified young people will continue to emigrate in high numbers and that the conflicts within the European Union will increase.

The first factor in Fidesz’s repeated land-slide electoral victory in 2018 was a general disillusionment with the Socialist government austerity policy before 2010, as well as Fidesz` rewriting of the democratic rules adopting a new constitution, changing the country’s electoral laws, and asserting government control over independent media.

The second factor of Orbán`s victory was that migration is still a winning issue. Since the European migrant crisis began in late 2015, migration had been ahead of all other issues in Hungary—in this respect, Orbán’s 2015 decision to close Hungary’s border and his continued defiance of EU requests to accept refugees have both been politically popular. Migration has proven to be an especially effective tool in mobilizing less educated voters, primarily in rural areas and in cities other than Budapest. Orbán has successfully persuaded his voters base that only he and his government can protect the country against the „Muslim invasion” and Brussels, George Soros, the Western liberals, and, most recently, the United Nations. On the surface, Fidesz’ strong position is largely based on the party’s tough opinion on refugees. When trying to explain the electoral success of Orbán and his party, however, one has to dig deeper and address broader fears in Hungarian society. Pessimism and a great extent of „dystopia” a negative future image, have always between a formatting power of Hungarian political culture. Many citizens have been exhausted by the ups and downs of the last decades; others fear that any changes might put the recent increases in wages and wealth at risk; some have lost their general orientation in a quickly changing world. Add Fidesz’s media dominance and the lack of a convincing (charismatic) opposition candidate, and these fears have made it relatively easy for Fidesz to play the xenophobic tunes.

The third major factor behind Orbán’s victory is his own success in uniting the right at a time when the opposition is weak and divided. Orbán has held his camp together for decades, using both economic and cultural nationalism to cement support from the more than two million voters who constitute the Fidesz base. In 2009, Orbán laid out a vision in which Fidesz could remain in power for decades if it was able to establish itself as the „central political force” with the opposition divided into left-wing and far-right blocs. After the collapse of the socialist party (MSZP) and the rise of the far-right Jobbik during the 2006–2010 term of parliament, Orbán’s prophecy came true, and Fidesz became the only major party in the Hungarian political landscape.

The Hungarian electoral system is designed for two main blocs, which does not fit the political structure of the country, and there were seven „major” competing opposition parties, so the result was well-known in advance. Electoral procedures such as voting rights and party registration and funding are arranged to dilute opposition support. More than 90% of traditional media outlets are now controlled by the government or allied oligarchs. The internet has thus become the central forum for public discourse and information, but this does not reach the population as a whole. There were many signs of electoral fraud, but the parliamentary parties did not fight for the detection of fraud quite firmly. It was a decisive win for Orbán, who in recent years has clashed publicly with the EU, becoming a forerunner of the illiberal ultranationalism rising not only in Central and Eastern Europe, but throughout the West, too.

Orbán`s electoral manifesto in 2018 consisted of only one sentence: „We’ll go on as before.” His messages to the Hungarians were: racist propaganda, xenophobia, no refugees, anti-Soros crusade, defending Europe`s Christianity and anti-communism. Orbán has not given interviews and participated in no debates. His victory is a product of several factors e.g. the weakening of the liberal democratic system, the success of anti-migration platform, and the extremely big fragmentation of the opposition. Orbán’s recent electoral success has strenghtened his position in Brussels, where Fidesz is still part of the center-right European People’s Party (EPP), the largest bloc in the European Parliament. While Orbán’s more provocative statements no doubt rankle EPP leaders, it is not lost on them that Fidesz’s eleven MEPs account for nearly half the EPP’s margin over the next largest parliamentary bloc, the Socialists and the Democrats.

Falsification of history

Fidesz government’s latest attempt to discover the „true” origin and history of the Hungarians Miklós Kásler, minister of human resources and one of those self-appointed amateur historians who are not satisfied with the accomplishments of professionals, established an institute that is supposed to „put an end to the hypothetical genetic and linguistic debate and reveal the truth based on science.”5

The perception of Hungary`s past history, the content of history books and the teaching are under constant changes. In 2000 Professor László Karsai wrote a detailed critique of history textbooks in which he severely criticized the apologetic treatment of the Horthy regime, the false and positive adjustment of Governor Horthy, and his government.

Right now, political attention is focused on the 1918-1919 period on account of its 100th anniversary. A full-fledged propaganda campaign is being waged by the rather large number of far-right leaders within Fidesz.

Today’s far-right historical revisionists try to picture Mihály Károlyi, PM of the first Republic as a promoter of the Soviet-style dictatorship of Béla Kun and a man whose ineptness caused Hungary’s harsh treatment at the hands of the Entente powers. Moreover, they charge, by allegedly letting the army disintegrate, he willfully abandoned Hungarian national interests. The fact is that the Hungarian army disintegrated on its very own. The soldiers scattered, and many of them burned the estates of landlords. Furthermore, according to the Agreement of Belgrade, Hungary could keep only eight military divisions. These same people accuse him of distributing his lands, which were in fact mortgaged, another baseless accusation.

According to the opposition, the falsification of Hungarian history is taking place on other filelds as well, e.g.

- Degradation of the events during the 133 days of the Hungarian Soviet Republic in 1919.

- Irresponsible political declarations in context with the Paris Peace Treaty signed at the Trianon Castle, at 1920, valid from 1921. This view of history greatly erodes the peaceful relationship with the neighboring countries, especially with Romania and Slovakia where great number of Hungarians live. During the last one hundred years, their percentage had been significantly reduced.

- The cleansing of history concerning the role of Hungary in World War II is also noticeable. Even a monument ”Hungary’s German Occupation of March 19th, 1994” has been built to one of the most important squares of Budapest. It is a blunt falsification of history, feeding populist rhetoric and appeasing Hungary’s far right. The statue had been commissioned and installed on Orbán`s orders. He wants to portray Hungary as a victim of Nazism, which is untrue. Hungary enacted Anti-Semite Laws as early as the 1920s, and the authoritarian government at the time received the Nazi occupation with open arms. That government collaborated with the deportation of thousands of Jews, gypsies and other political dissidents. Orbán’s statue seeks to absolve the Hungarian people of their role in the death and deportation of 600,000 Jews. In fact, Hungary’s right-wing government passed anti-Semitic legislation as early as 1920, and “the Nazis were welcomed not with bullets but with bouquets of flowers.”6

- The conflation of the so called Communist era, (in fact and in reality pre-Socialist era) what the course historians deliberately confuse and make no difference between the Stalinist times before the 1956 revolution and the Kádár era, when (especially between 1970 and 1985.) the political and economical recognition of Hungary was the best in the world, and the Hungarian model was envied among the countries of the region. Upon this topic it is important to see the removal the statues of Mihály Károlyi PM of the first Republic, and that of Imre Nagy the PM of the 1956 revolution from Kossuth square (where the Hungarian Parliament stands).

Democratic institutions being hollowed out. Assault on CSOs and higher education

The ruling Fidesz party is highly centralized. The government has set up a broad, well-financed network of false, pro-government civil-society organizations and foundations, like the Civil Cooperation Forum (CÖF). At the same time Orbán continues war against Civil Society Organizations (CSOs). In the first major legislative moves since Orbán won reelection last spring, the Hungarian Parliament on 20 June 2018 passed a package of measures that is a continuation of Orbán’s efforts to weaken civil society and any other checks on his government’s control over life in Hungary. The most direct attack on CSOs came from a new law that criminalizes the act of assisting – or even providing information to – refugees seeking political asylum. Another measure passed, a change to the Constitution that makes it easier for the government to control the judiciary, may eventually do even more damage to civil society and any efforts to protect human rights in Hungary. An additional alteration of the Constitution codifies the government’s refusal to accept refugees, and appears to be a challenge to the authority of the European Union.7

The government has continued to hollow out the institutions of democracy. It has demonstrated little trust in the soft power of its huge propaganda industry and has stepped up efforts to weaken the opposition while undermining the remaining checks and balances. It has limited the opposition’s access to the public by restricting opposition parties’ use of billboards, which had played an important role in the 2010 and 2014 election campaigns. It has further tightened its control over the media, as the last four remaining regional dailies were bought by oligarchs close to Fidesz in July 2017; it has massively campaigned against independent, foreign-funded NGOs and introduced a new law that makes their work more difficult; and it has sought to close the Central European University (CEU), which is not only the country’s most prestigious institute of higher education but is also a stronghold of independent thinking. The assault on CSOs and the CEU has been part of a massive campaign, marked by anti-Semitism, against the Hungarian-American millionaire-philanthropist George Soros. The government’s anti-Soros campaign has invoked anti-Semitic stereotypes. As a centerpiece of Fidesz’s election campaign, these efforts have been closely linked to Fidesz’s ongoing anti-refugee and anti-EU rhetoric. Opposition activists are defamed as traitors and foreign agents. Discrimination against minorities, especially Muslims, Roma and refugees, is widespread. Asylum-seekers are subject to forced detention. Judicial independence has declined substantially, and corruption is pervasive.

By mid-2017, a new nationalist coalition emerged on Hungary’s far right. The coalition was seen as challenging the ex-leader Gábor Vona’s effort to move Jobbik leftward toward Hungary’s political center. The gap created by Jobbik’s recent changes needed to be filled, Fidesz seemed to want the new extreme right-wing movement to become a party itself and weaken Jobbik in the national elections.

A new radical nationalist political force, Our Country Movement (Mi Hazánk Mozgalom-MHM), appeared from the dissatisfied Jobbik members as well as from the radical nationalist groups. MHM founder László Toroczkai is a former Jobbik deputy chair and the mayor of Ásotthalom whom the party expelled in early June after a failed leadership challenge.

By the middle of 2018 a completely new political era has been consolidated in Hungary. A limited political pluralism has evolved over the past eight years, a national radical, but superficial ideologized system, namely a racist and a corrupt one, but lacking a strong world view. Orbán`s regime is an opressive semi-dictatorial system. Electoral gerrymandering, curtailing press freedoms and fearmongering create a toxic mix to consolidate rule over the people. There is no counterpower, not even in his own party. Orbán`s will cannot be challenged, his decisions are final, non-appealable, implemented by loyal bureaucrats. The strong position of the fourth Orbán government means that democracy in Hungary will continue to erode, pervasive corruption will undermine both democracy and economic growth, societal polarization will continue, the rift between liberal Budapest and the more traditional countryside will grow, qualified young people will continue to emigrate in high numbers and that the conflicts within the EU, not only over the issue of migration, will increase.

Not only the opposition is divided between the left and the far right, but the Left itself is highly fragmented, meaning there is no single center-left party comparable to Fidesz’s position on the center-right. Hungary’s Left and liberal opposition parties learned nothing from their 2014 electoral fiasco, in which their failure to coordinate allowed Fidesz to win another supermajority. For most of the 2018 campaign—and despite huge pressure from the majority of Hungarians who wanted a change—left-wing and liberal parties competed with each other over who would dominate the Left in the future, rather than working together to replace Fidesz.

However, we can see a new kind of opposition since early December 2018, which is not an issue of initiative, unity and symbolic politicization. The attitude of the opposition to Orbán’s system changed fundamentally.

On 8 December 2018 a wave of mass demonstrations started by the trade unions to protest against the planned changes to the labor law dubbed as „slave law”, which include raising the maximum amount of overtime workers can put in a year from 250 to 400 hours and relaxing other labor rules. The legislation also gives employers three years instead of one to settle payments of accrued overtime. Another amendment allows employers to agree on overtime arrangements directly with workers, by passing collective bargaining agreements and the trade unions.

On 12 December the amendment of labor and other controversial laws amid scenes of chaos were also adopted as opposition MPs attempted to block the podium of the parliament and sounded sirens, blew whistles and angrily confronted Orbán. Hungary’s parliament was thrown into scenes of turmoil. The opposition claimed that the voting procedure was completely against the House Rules and was invalid.

Since 12 December the mass demonstrations have been going on continuously and every night, in average 30-50 people were arrested daily after clashes with the police which was using tear gas. The protests in Budapest and in other towns have never been so violent since Fidesz came back to power in 2010. The protests were led by the so far divided trade unions and opposition parties (including Jobbik) and students, which had been outraged at the reforms Fidesz recently introduced.

Corruption, crony capitalism pervasive. Recovery based on EU funds

Hungary’s political system, economy and society have been linked by pervasive corruption and a special variant of crony capitalism. Hungarian society has increasingly taken on the features of a proto-feudal system in which the supporters of the regime benefit from corruption and nepotism. Economic policy has been characterized by an increasing „re-nationalization” of the economy and a „re-feudalization” of public procurement. The Orbán government’s decisions are largely meant to provide investments and business opportunities for his own network. As a result, the recovery of the Hungarian economy since 2013 has been strongly based on the influx of resources from European funds and on investment in stones rather than brains. Given the fact that the education and R&I systems have been subject to chronic underfinancing, political control and dubious organizational reform and that the shortage of qualified labor is growing, Hungary’s medium-term economic perspectives look bleak. To consolidate his political power, Orbán is combining the economical and political power and works with limited amount of loyal oligarchs. The most powerful one is: Lőrinc Mészáros. According to Forbes, by the end of 2018 he became the wealthiest Hungarian, as last year he tripled his wealth. Mészáros comes from the same village of Orbán, whose population is 1,400. Mészáros says „I am lucky, because God helps me”.

Some reforms, but without consultation

Since 2010, the Orbán government adopted a number of institutional reforms that has centralized power, facilitating patronage and ideologically driven decisions. High-level government reorganizations seem aimed at creating elite rivalries. Agencies are closely monitored. The government’s conflicts with the EU have deepened over time, particularly with respect to the issue of refugees.To underline its reform commitment, it created a new Competitiveness Council and announced the creation of a cabinet committee on family affairs. In October 2017, in a campaign-driven move, it also appointed two new ministers, thereby continuing the government’s proclivity to create top-level positions for its allies. While Orbán back in 2010 emphasized the need for small government, his government in fall of 2017 consisted of 178 ministers, state secretaries and deputy state secretaries, twice the number of PM Bajnai`s government in 2010. At the same time, policymaking has continued to suffer from over-centralization, hasty decisions and the renunciation of public consultation and external advice.

EU is last remaining veto player. Patience with Orbán wearing thin

Due to the fact that the Hungarian institutions meant to counterbalance the power of the government – such as the Constitutional Court, the media and the president of Hungary – have failed to fulfill their mandates, the EU is the last remaining veto player. Indeed, as the EU has repeatedly made a point of highlighting corruption, administrative shortcomings and illegal practices in the Hungarian government, Brussels is unsurprisingly increasingly attacked as an enemy in the eyes of the Orbán government. On October 23, 2017, an important national holiday, Orbán held a campaign speech in which he began by drawing a parallel between the former „homo sovieticus” and the „homo brusselicus” as a historical burden of Hungary and closed by stating that „true Hungarians” would vote for Fidesz. In its confrontation with the EU, Fidesz has focused primarily on two ongoing infringement processes in political matters and the European Court of Justice’s refusal of Hungary’s attempt to sue the EU on the issue of refugee allocation to demonstrate its commitment to an alleged fight for freedom. These campaigns, together with several other anti-EU measures have deepened the conflict between the Hungarian government and the European Commission and the broad majority of EU members states. Even within the European Peoples Party, the patience with Orbán has worn thin.

Economic Policies

GDP growth rebounded strongly after a slowdown in 2016, benefiting from the resumption of EU-funded investment, a fiscal stimulus, negative real interest rates and strong wage increases. Growth has primarily been driven by fixed capital formation such as large construction projects (like building sport arenas, i.e. football stadiums), as well as household consumption. Unemployment rates have dropped significantly in recent years, in large part due to a broad public-works program that rarely produces long-term labor-market integration. Significant emigration has also played a role in the decrease of the rate, creating a brain drain that has led to skilled-labor shortages in many fields (e.g. in hospitality industry, or industrial companies, mainly in West-Hungary, near the Austrian and Slovakian border). Tax reforms have shifted the burden from direct to indirect taxes. Significant tax reductions have been implemented in recent years, with larger companies seeing particular benefit. However, frequent tax changes still complicate economic activity. The research sector remains fairly advanced, but is underfunded and the autonomy of the Hungarian Acedamy of Sciences (MTA) has been curtailed.

According to the Hungarian Central Statistical Office (KSH) in 2018 the real GDP growth rate was 4.8 percent, which is almost double of the EU-average. Growth was boosted by soaring domestic demand. Fixed investment continued to surge, fueled by inflows from EU funds and sturdy construction production, while robust wage growth and an extremely tight labor market powered solid consumer spending.

In 2019 growth is expected to soften. Particularly, a slowdown in EU fund inflows will translate into a less impressive expansion in fixed investment, while higher inflation and fewer job gains will drag on consumer spending. Economic growth will slow to an average of 2.3% in 2019-23 as external demand slows. The current-account surplus is set to increase in 2019-20, before shrinking as world oil prices recover in 2021-23. Large public and external debt levels remain sources of risk.

Social Policies

Major education-system reforms, including spending cuts and centralization, have undermined student outcomes. A controversial higher-education act has sought to drive the Soros-funded CEU out of Hungary. Poverty is worsening, and the middle class is being further weakened. Roma are still deeply marginalized, particularly with regard to education and employment.

Health care is a highly conflict-ridden area, leading to a series of scandals and protests. Problems include widespread mismanagement and corruption, hospital debt, and a brain drain of medical staffers. Support for families is tied to anti-immigration policies. Child care has been expanded, and counseling centers created to help women combine parenting and employment, despite Orbán`s controversial new family support package8.

Disparate pension systems have been merged, but pensioner poverty has increased. The government has taken a strongly xenophobic anti-refugee stance both domestically and in an EU context. However, non-EU citizens can obtain Hungarian passports in return for investments in the country.

Environmental Policies

Hungary has comprehensive environmental laws, strongly influenced by EU policies. However, the issue has not been a focus for the Fidesz government at all. Under Fidesz rule the Ministry of Environment, same as the National Inspectorate for Environment and Nature Protection ceased to exist. This Activity today belongs to a fully-weightless state secretariat in the Ministry of Rural Development. Policy has thus been fragmented, and problems such as drinking-water contamination and waste-site mismanagement, as well as air-pollution have grown significantly. Rampant construction in Budapest green areas (e.g. in Városliget/Budapest - municipal park) has led to the loss of many trees.

The country is expanding its use of nuclear power, with work on a key plant financed by Russia, still strongly contested by the Austrian government. This will likely help reduce CO2 emissions, but has also resulted in a neglect of renewable power sources.

Population still supports EU9

A survey in late 2017 found that the overwhelming majority of Hungarians supports liberal democracy (79%) and favor staying in the EU (71%). The democratic opposition tried to capitalize on this sentiment by formulating the issue at stake in the parliamentary elections as „Europe vs. Orbán” though without success. The key challenge of the future is to bring this support to the forefront and to diminish the growing influence of right-wing populism in Hungary. In this process, the government will not be of help, but rather the target.

TÁRKI`s Report on Society in 201810

Last November the Hungarian social research institute TÁRKI presented the latest edition of its Social Report, their biannual publication summarising the most important social indicators and social trends of Hungary. The collection includes 22 studies delving deep into questions of social mobility, integration and disintegration, examining the pitfalls of Hungary's education system, taking a look at the secluded elite and the closure of society. Of the 22 studies three in particular caught the imagination of the independent Hungarian media: Ágnes Hárs’s study on emigration, Judit Lannert on education, and Péter Szívós on economic development and convergence.

Increasing emigration11

Ágnes Hárs’s study was the most shocking because of her finding that by now 8% of all Hungarian college graduates live abroad —a trend likely to continue growing until Hungarian salaries are at least half of the western European average. More thoughtful Hungarians have been deeply worried for some time about the relatively high emigration rate, but this is the first time they could see in black and white that the most rapidly growing segment of the emigrants are the most highly educated. Interestingly enough, the data presented by Hárs didn’t seem to bother the Orbán government. In fact, the article by „Binkmann” starts by asking „What is wrong with Hungarian college graduates holding their own abroad?” Of course, nothing, if they decide to return and apply their newly-found knowledge and experience at home. But we know that in most cases this is not the case.

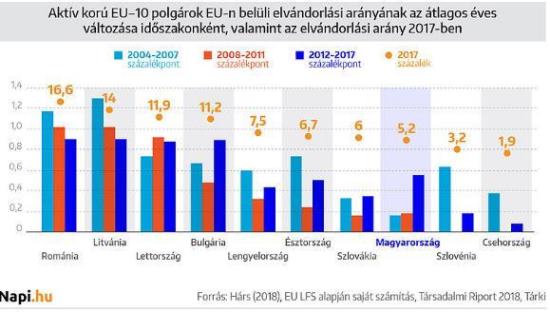

Hungary, along with Poland, Estonia, and Slovakia, belongs to the countries of „moderate emigration tendencies” as opposed to Latvia, Lithuania, Romania and Bulgaria, where emigration is much higher. As of 2017, 5.2% of the Hungarian population between the ages of 20 and 64 lived abroad as opposed to Romania’s 16.6%.

Before 2011 emigration from Hungary was low, but then it shot up rapidly and has been growing since. According to Hárs’s calculation, each year about 30,000 people leave the country, mostly to the United Kingdom, Germany, and Austria. Who are these people? The Hungarian pattern of emigration is fundamentally different from the other nine countries from the former socialist camp. While in the other countries the bulk of the emigrants come from the less educated strata of society, the Hungarian situation is exactly the opposite. Relatively few people of modest educational attainment leave, and a very large portion of the emigrants come from groups who are in possession of a matriculation certificate and/or who finished college. This tendency had been notable in the Hungarian emigration statistics ever since 2004, but after 2011 it accelerated. Every year between 2012 and 2017 the emigration of college graduates grew by 0.7%. As a result, in 2017 8% of Hungarians with university degrees lived and worked abroad.

|

The most highly qualified and best educated younger people normally head to the United Kingdom, while those without a degree and those who were unemployed in Hungary go to Germany.

What are the reasons for the accelerating emigration? First and foremost, the incredible wage differences between the better developed original EU members plus Norway and Switzerland on the one hand and Hungary on the other. Hungarian wages are 50% of the average of EU-15+2. As long as this situation exists, one cannot expect a slowdown in the population flight from the country.

At the same time one cannot ignore the above graph, which shows the size of emigration between 2012 and 2017 and before. One must assume that the political environment that Orbán has been building since 2010-2011 has had an impact on people’s willingness to start a new life elsewhere. What most Hungarians who have been living in Western Europe for some time complain about is the lack of opportunity in Hungary for those without personal connections. In Hungary meritocracy is an unknown concept. Then they leave and suddenly discover that they can succeed on their own and that their hard work and talents ensure their professional advancement. They conclude that returning to Hungary would not be to their advantage. Of course, a fair number of people do return, but their numbers are unknown. One assumes that the returnees are the ones who didn’t adjust well to their new surroundings or who had difficulties learning the language.

Another reason for the growing emigration of young people is the so-called reform of the education system, which turned out to be a return to the old method of teaching from the 1970s. In addition, the Orbán government introduced steep tuition fees at institutions of higher learning in comparison to wages. And ever since 2012-2013 uncertainties have plagued the education system, from kindergarten to university. Everything is in constant flux. The government is constantly experimenting with the children of its citizens. More and more parents are discovering that the antiquated methods of teaching kill their children’s enthusiasm for learning. Test scores show Hungarian students’ performance getting lower year after year. Parents often pack up and move abroad because they want better education for their children. The prospect of bilingualism is also attractive, especially since children in Hungarian schools in the majority of cases never learn to speak any foreign language.

Western Europe Continues to Attract Hungarian Graduates12

Ágnes Hárs’ emigration report, published in the TÁRKI`s Social Report, points out that eight to ten percent of the 4-4,5 million Hungarians (an estimated of 350-600,000 people) in the labor market are now working and studying in other countries. The proportion of emigration with tertiary education is unique and the highest among European countries.

According to Hárs, the number of graduates in Hungary also exceeds the average. In 2017, 5,2 percent of the working-age population emigrated. With this result, Hungary—just like Slovakia, Poland and Estonia—is one of the few countries with moderate emigration. Romania has the highest number as 16,6 percent of 20-64-year-olds lived abroad last year.

The study shows that the main problem in Hungary is that the proportion of qualified people leaving the country is higher. Apart from graduates, the most significant increase can be seen among young people and entrepreneurs. On the other hand, the rate of emigration of those with lower qualifications is lower in Hungary.

The researcher estimates that the number of emigrants exceeded 300,000 last year and has increased by at least 1 percent each year since 2010. Additionally, around 2 percent left their jobs with the intention of moving and working abroad. Taking those who return into account, on average, net 1 percent of the labor market went abroad on a yearly basis. The most significant results can be seen in hospitality, construction, manufacturing and sectors that are heavily affected by the labor shortage, such as healthcare.

According to Hárs, the persistence of the sudden and rapid growth rate cannot be predicted, but the continuance of the trend can. This is partly caused by the significant wage gap. Hungary is in an unfavorable position as salaries are much lower here than in other countries.

In recent studies, Hungary was among the most marginalized countries in terms of income. In fact, it barely exceeded half of the average income of Western European countries. Although the situation has improved somewhat over the last few years, Hungarian emigration appears unlikely to slow down.

No country for children

Judit Lannert's study titled "No country for children - Hungarian education and 21st-century challenges" reveals that the most important indicators place the Hungarian education system amongst the weakest in Europe. Public education is burdened by overstuffed curriculums and improper pedagogical methods, creating a lack of motivation in pupils and amplifying the handicap of disadvantaged students. The most recent PISA tests show a decrease in mathematical performance and a steep fall in the students' trust in their ability to efficiently tackle problems and show that Hungarian students rank last in Europe in digital literacy despite the country's relatively high rate of internet penetration and time spent browsing the internet. The study concludes that the Hungarian society is in a state of „future shock", referring to the term coined by futurologist Alvin Toffler.

Future Shock13

István György Tóth, one of the editors of the TÁRKI`s publication remarked that the political elite started to underestimate the importance of education. He said there is a trend in Hungarian education policy that encourages children to specialise as soon as possible, favoring vocational training over lifelong learning. According to him, this attitude submits education to the day-to-day needs of the job market, and it goes against the tough demands set by the current pace of technological progress. Vocational knowledge turns obsolete fast, and this phenomenon requires people to possess a flexible set of skills to remain competitive. The current approach of the political elite - discouraging flexibility, innovation, curiosity - is running a high risk of the country falling into a negative spiral that might create a social division with one distinct part of society that will be able to compete in a globalised economy and another one that falls behind and becomes an easy target for political manipulation due to their growing frustrations.

Austria is far away, but catching up to Portugal in ten years seems possible14

Reaching the Western-European standard of living is a long-standing goal of the Hungarian society. Péter Szívós's study titled „Is Europe far away?” compared Hungary's most important social and economic indicators to those of Western and Eastern European countries, Austria and Portugal, and Poland and Romania respectively.

The study found that Eastern European countries had a more dynamic development in terms of per capita gross national income than their Western counterparts, but Hungary's development is the least dynamic within its group. Hungary's 48% higher education enrollment rate may seem like a huge leap from the 15% it was at the time of the regime change of '89-'90, but it doesn't look so good when compared to the 68% it was in 2007. The current figure matches Romania's enrollment rate but pales in comparison to Austria's 83%.

The 2016 data for life expectancy at birth shows improvement in all examined countries, but the earlier differences remained the same. The current figure in Hungary is 76 years, while those born in neighbouring Austria are expected to live 81 years.

The indicators show that Austria still preserves its advantage, but the other countries featured in the study are slowly catching up. The difference between Hungary and Portugal is diminishing at a faster rate, which means Hungary could reach the level of the less developed Western European countries within the next ten years, though Hungary is ranking lower amongst the post-socialist countries than before.

Social Divide15

Another study from TÁRKI, entitled „Building Nations with Non-Nationals” shows how hard it is to get into the upper-middle class, the top 10-20% of Hungarian society. The social differences are not as big in Hungary as they are for instance in the United States, but social mobility is very low, explained Iván Szelényi, an author of the study. In European terms, income disparity is generally low, but this value is exceedingly high within groups affected by severe material deprivation. The top 10% of society is completely secluded from the rest. Entry into that elite is becoming increasingly difficult, but due to its highly self-reproductive nature it is a status that is difficult to lose.

Szelényi added that a wealth of HUF 70 million (EUR 220,000) already places one in the top 5% - a sum equivalent to the value of a moderately nice flat in one of the more expensive neighbourhoods of Budapest.

The study of Márton Medgyesi and Zsolt Boda examines the public trust placed in institutions, an important topic due to the effect of this trust on the ratio of norm following behaviours. In recent years, Hungary has been experiencing changes in this trust, especially in political institutions. Even if trust in public institutions in general was mostly on the rise during the past ten years - even during the financial crisis in the 2007-2011 period - the trust in political institutions shows a different pattern. After the political turmoils of 2006, there was a general erosion of trust in politics, but a shift occurred in 2010: since then, those with right-wing political convictions seem to increasingly trust political institutions, while the declining trend is continuing on the left. It seems that the trust in political institutions became strongly dependent on the political sentiments of the individuals and the coloration of the current government.

Will Hungary’s Dream Come True?16

Throughout the 20th century, Hungarian politics has been haunted by one question: how can Hungary catch up to the economically advanced countries of the West? It seems the more Hungary’s politicians ponder this question, the more elusive the solution appears.

Hungary’s role model has always been Austria, at least when it comes to communication. When Austria-Hungary split up, the Hungarian national income per capita reached 85 percent of Austria’s GNP. According to World Bank data, Hungary’s per capita GNI measured in purchasing power parity was approximately half of the value of Austria’s in 2015.

How far can Hungary get?17

Since 1990, TÁRKI Social Research Institute has been publishing its Social Report which reflects vital cultural and economic changes in Hungarian society. The government has supported the study since its inception. “Is Europe far away?” author, Péter Szívós, presented his findings to the press. The researchers have compared Hungary’s economic and social indicators with those of two older Member States (Austria and Portugal) and two regional competitors (Poland and Romania).

According to the study, after the era of transitions, Eastern European countries experienced more GDP growth than Western European countries, but Hungary’s results have been the most moderate among CEE countries.

In regard to higher education, Hungary improved its position. When socialism collapsed, student enrollment rates were 15 percent, but by 2007, that number increased to 67 percent. Unfortunately, over the last 8 years, Hungary’s number of students has decreased, matching Romania’s.

In terms of life expectancy at birth, each surveyed country improved, but the differences couldn’t be eliminated entirely. In 2016 in Austria, the life expectancy was 81 years. In Hungary, this number was a slightly lower 76. It will be hard, if not impossible, to catch up with Austria. However, it’s plausible that Hungary’s economy could be on the same level as Portugal’s in just ten years.

The Hungarian National Bank (MNB) hopes that Hungary can catch Austria by 2030

The Central Bank of Hungary (MNB) published an optimistic growth report18 and its director, András Balatoni, presented the document’s main points on InfoRadio. The report resembles „180 Steps for the Sustainable Convergence of the Hungarian Economy,” an earlier document issued by MNB. The document sets ambitious macroeconomic targets for the year 2030, which, according to the study, could be attainable through the implementation of 180 measures. The study also proves that in light of comparison with international statistics, Hungary’s economic progress should be based on qualitative rather than quantitative growth.

As a result of the competitiveness reform planned by MNB, productivity may improve. In ten years, nominal wages could double, and with full employment, a GDP growth of 4-4.5% could be reached permanently.

This growth is essential for Hungary to close the gap, Balatoni said. The director also suggested that with a single-digit personal income tax, increased productivity and discovery of hidden economic reserves, Hungary could approach Austria’s level of wage development by 2030. Balatoni`s report is to be considered as a „mandatory treasury optimism” ordered by György Matolcsy, Governer of the National Bank of Hungary upon Orbán`s request.

Budapest, 17 March 2019.

References/Useful Links

http://ensz.kormany.hu/a-2030-fenntarthato-fejlodesi-keretrendszer-agenda-2030-

http://hand.org.hu/media/files/1450115684.pdf

http://ensz.kormany.hu/download/

http://www.nfft.hu/voluntary_national_review

http://eionet.kormany.hu/fenntarthato-fejlodesi-celok-megvalositasa-magyarorszagon

https://sdgcompass.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/10/SDG_Compass_Guide_Hungarian.pdf

http://utajovobe.eu/hirek/energetika/7743-veget-erhet-az-europai-szenhaboru

https://ensz-newyork.mfa.gov.hu/

https://ensz-newyork.mfa.gov.hu/

https://knowledgehub.transparency.org/assets/uploads/kproducts/SDG_Parallel-Report_2018_Hungary.pdf

https://www.sdgwatcheurope.org/hungarian-ngos-establish-a-roundtable-on-sdg-implementation/

http://ffcelok.hu/a-celok-hazai-megvalositasa/

https://www.ksh.hu/sdg/cel_01.html

http://ffcelok.hu/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/HAND_SDG_indikátorok.pdf

https://profitline.hu/A-vallalatok-csupan-28-a-tesz-a-fenntarthato-fejlodesi-celokert-387905

https://www.pwc.com/sdgreportingchallenge

http://ffcelok.hu/wp-content/uploads/2018/05/MSZEH_szegénység_éhezés_oktatás_egyenlőtlenségek.pdf

https://24.hu/tudomany/2019/02/10/szazezrek-elnek-hazankban-ugy-hogy-ok-nelkul-szegyenkeznek/

http://eionet.kormany.hu/fenntarthato-fejlodesi-celok-megvalositasa-magyarorszagon

https://www.mnb.hu/letoltes/novekedesi-jelentes-2018-digitalis.pdf

https://www.mnb.hu/letoltes/growth-report-en.pdf

https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/hlpf/2019

https://index.hu/english/2018/11/07/hungary_society_report_2018_tarki/

https://index.hu/belfold/2018/11/06/tarsadalmi_riport_2018_magyarorszag/

https://infostart.hu/belfold/2018/11/20/ujratermelodik-a-tanulatlansag-e...

http://hungarianspectrum.org/2018/11/13/kopint-tarkis-report-on-society-...

http://hungarianspectrum.org/2018/11/11/kopint-tarkis-report-on-society-...

http://www.sgi-network.org/2018/Hungary/Social_Policies

http://www.sgi-network.org/docs/2017/country/SGI2017_Hungary.pdf

https://hungarytoday.hu/will-hungarys-longstanding-economic-dream-come-t...

https://hungarytoday.hu/western-europe-continues-to-attract-hungarian-gr...

http://www.tarki.hu/sites/default/files/2019-02/013_031_Speder.pdf

https://www.tarki.hu/sites/default/files/2019-02/032_045_Harcsa_Monostor...

Notes:

2 Index- Külföld of 17 October 2018 (Hungarian portal, web daily news)

3 http://portofolio.hu/ and RTL Klub News of 27 March 2017.

4 http://szakszervezetek.hu/ Független hirügynökség of 7 May 2018.

5 http://hungarianspectrum.org/2019/01/12/conservative-revolt-against-falsification-of-recent-hungarian-history-by-the-fidesz-far-right/

6 Leon,D., Orbán`s falsification of history in Budapest, 22 September 2017. https://leipglo.com/2017/09/22/orban-falsification-history-budapest/

7 Popper,T. ,Orban continues war against civil society, 3 July 2018. https://bluelink.info/rights-and-equity/orban-continues-war-against-civil-society/

8 Kovács,Z. "No future for mixed nations" - Orbán kicks off EP campaign https://index.hu/english/2019/02/10/

10 Német,T.:Report on Hungarian Society: Portugal on the horizon, Austria still far away, https://index.hu/english/2018/11/07/hungary_society_report_2018_tarki/

16 Sarnyai,G. Will Hungary’s Longstanding Economic Dream Come True? https://hungarytoday.hu/will-hungarys-longstanding-economic-dream-come-t...